The past few years have seen substantial growth and expansion of digital strategies in the art world, adopted in a number of variations by galleries, art fairs, and institutions; these platforms are important to expand audience reach but do little to push conceptual boundaries within the digital realm. Library Street Collective has developed a unique digital connection between the visual arts and the built environment, incorporating aspects of storytelling, architectural history and an artist’s unique perspective through the presentation of SITE: Art and Architecture in the Digital Space. Each exhibition featured within this digital platform will respond to its environment - making connections between art and place.

Library Street Collective has engaged renowned architectural photographer James Haefner to help realize the vision for SITE. Haefner is featured in 'Michigan Modern: Design that Shaped America' and co-creator of 'Michigan Modern: An Architectural Legacy.' The photographer has been key in capturing the architectural imagery for SITE, and because the presentation is entirely digital, he has skillfully and seamlessly rendered the artwork into each environment.

As a means to positively impact our community, Library Street Collective will be donating 10% of the proceeds on any works sold during SITE: Turkel House to Freedom House Detroit, a temporary home for indigent survivors of persecution from around the world who are seeking asylum in the United States and Canada. Guided by their belief that all persons deserve to live free from oppression and to be treated with justice, compassion, and dignity, Freedom House Detroit offers a continuum of care and services to their residents as well as to other refugees in need. The group advocates for systemic change that more fully recognizes the rights of asylum seekers.

At Freedom House Detroit, asylum seekers without resources receive shelter, legal aid, employment readiness training, and access to healthcare. "Freedom House [Detroit] works hard to give us hope. Hope of peace, hope of love, hope of freedom." (P.A. A, Freedom House Detroit Alumnus)

Turkel House

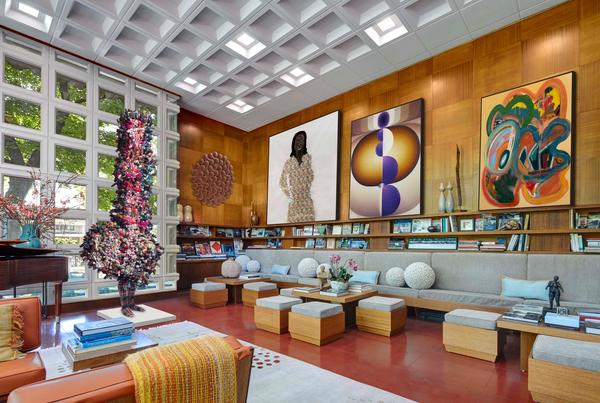

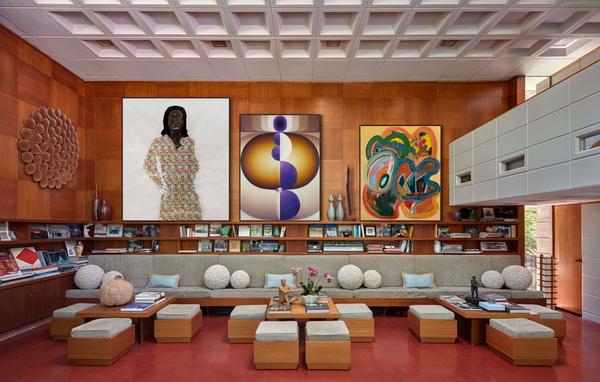

The newest iteration of SITE is set against the organic architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Dorothy G. Turkel House. The only of Wright’s works within Detroit’s city limits, the house was completed in 1958 and remained the home of its namesake until the mid 1970s.

Photo by Balthazar Korab

In the years succeeding her ownership, the house faced decades of deferred maintenance and vacancy, and was at significant risk of ‘demolition by neglect’ despite its protection as a City of Detroit landmark. By the summer of 2006, the house was in mortgage foreclosure and would require preservation-minded buyers in order to save it.

Working from original archived blueprints, buyers Norm Silk and Dale Morgan hired former Wright apprentice Lawrence Brink to lead the project and spent over 4 years in the pursuit of its rehabilitation. The Turkel House is an example of one of Wright’s Usonian Automatic designs, which grew out of the Usonian construction he originated during the Great Depression. Usonian - which Wright said was short for United States of North America - was a style the architect conceived to realize ‘mass customization’ of homes for the middle class that would reflect the American spirit. The Automatics were built from a concrete masonry system that Wright created in 1949, and though there are hundreds of Usonian homes in existence throughout America, only 7 are Automatics, with the Dorothy G. Turkel house as the largest and the only one built with 2 stories.

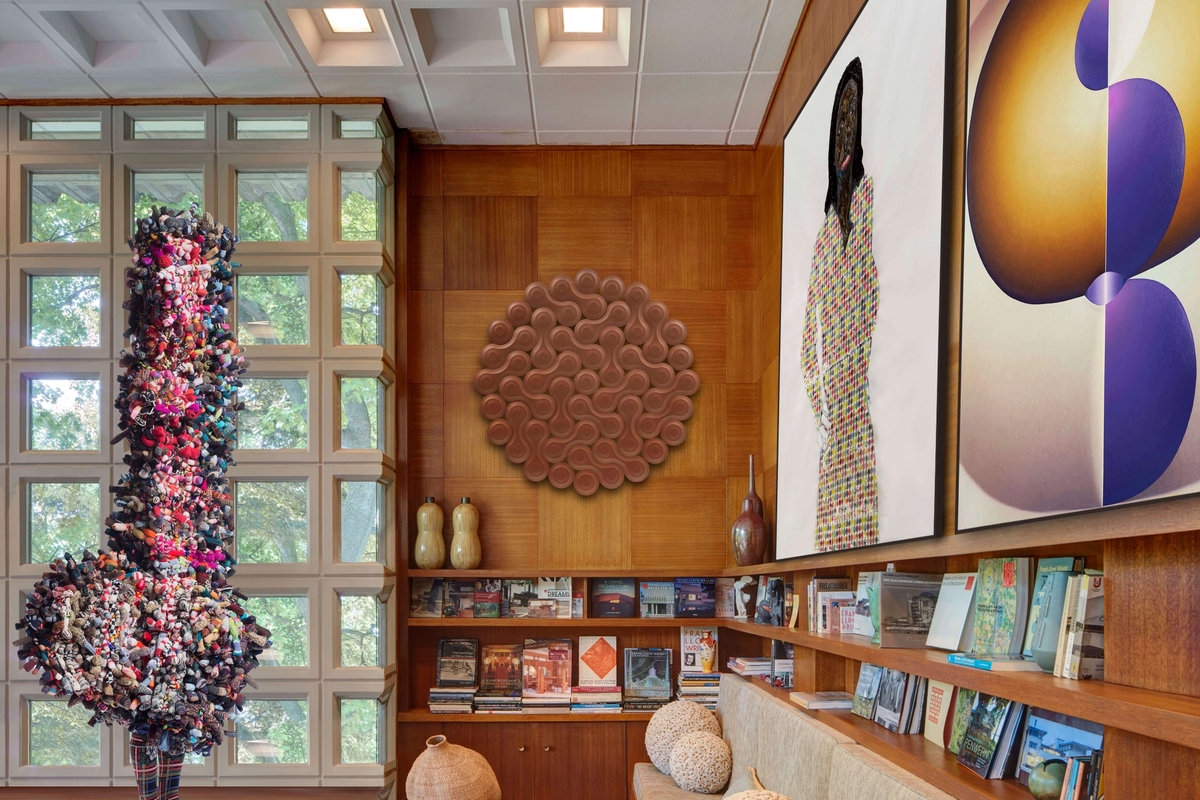

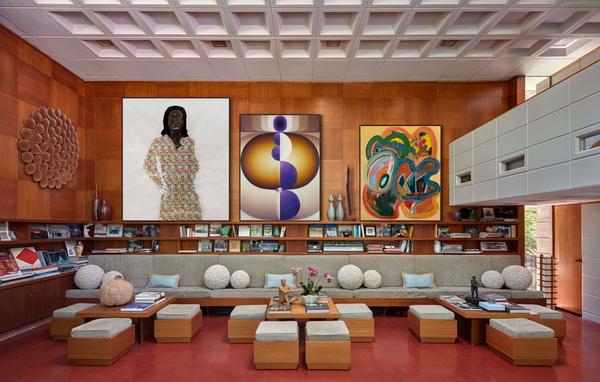

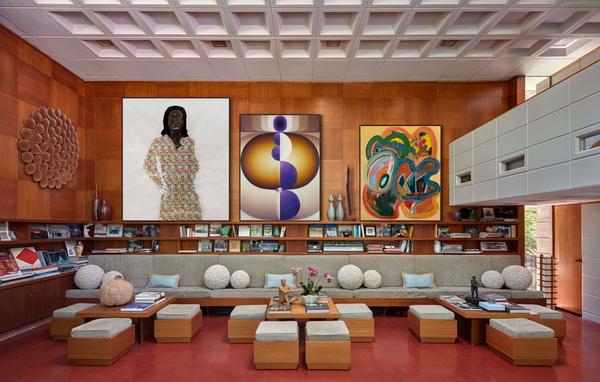

Installation Images

For Wright, Usonian architecture provided the building blocks for mass customization as an idealized vision of the United States at its democratic zenith. The architect’s language of geometries, materials, and systems parallel that of the artist, whose unique vocabulary of ideas and forms translate as an essence that carries from work to work throughout their career, always at the service and encouragement of the viewer’s personal and social progress. It is against this backdrop that we examine the elemental and progressive ideas at play within the works of artists Amoako Boafo, Nick Cave, Beverly Fishman, Loie Hollowell, Tony Matelli, Josh Sperling, Frank Stella, Hank Willis Thomas, Blair Thurman, and Austyn Weiner.

SITE Artists

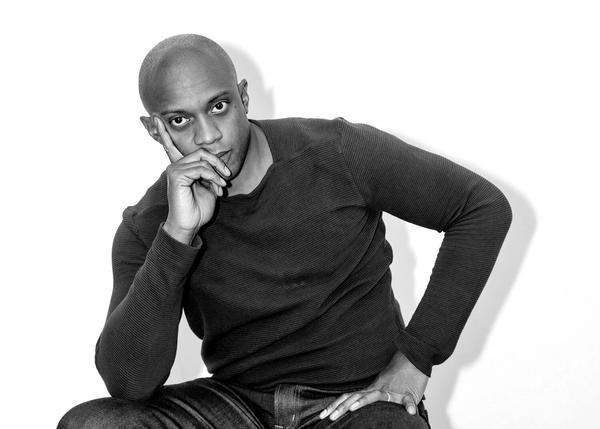

Amoako Boafo

Amoako Boafo is a painter, born in Accra, Ghana, and based in Vienna, Austria, whose sinewy portraits are captivating in their transparency. Often isolated on flat monochromatic backgrounds, the artist’s figures accentuate flesh made with flesh, with Boako creating finger-painted channels that rise and fall across the skin. Another important characteristic of the artist’s work is the use of photo transfer to reproduce found patterns in his subjects’ clothing; a contrast that finds energy between the tactile treatment of the skin and the burnished pictographic fabrics. Like Boafo himself, the men and women in his portraits are always well-dressed, and the artist is inspired by traditional English fabrics, Liberty print gift wraps and reproductions of wallpaper from the Victoria and Albert Museum. Much of his work is inspired by his upbringing in Ghana, often challenging the belief that boys must be raised to be aggressive and masculine when they’re grown: “The primary idea of my practice is representation, documenting, celebrating and showing new ways to approach blackness.”

“I use painting as an instrument to navigate the complexities of human experiences and to depict a sense of each subject’s presence in the world. I place my subjects at a higher recognition, in size, and in terms of their gaze at the audience. Each gaze in my subjects functions to disrupt viewership. I want to bring to light sentiments of how black people are constructing identity.”

— Amoaka Baofo

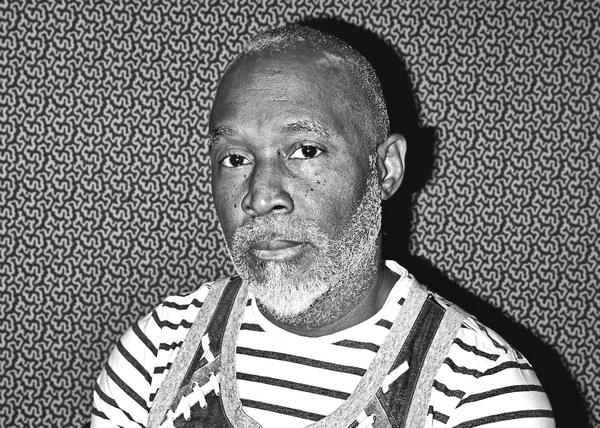

Nick Cave

Nick Cave is an artist, educator, and messenger, working between the visual and performing arts through a wide range of mediums including sculpture, installation, video, sound, and performance. The artist is perhaps best known for his Soundsuits, which are sculptural forms based on the scale of his body that were created in response to the police beating of Rodney King in 1991. What began as an armor of sticks sourced from a local park, these wearable sculptures have grown and changed in a number of dynamic and emotional iterations, using found objects to create a second skin that conceals race, gender, and class, and forcing the viewer to look without judgment. His works serve as a visual embodiment of social justice that represents brutality and empowerment simultaneously. Through his roles as artist, educator, and social activist, Cave encourages a profound and compassionate analysis of violence and its effects as the path towards an ultimate metamorphosis.

“I was building this suit of armor, something that I could shield myself from the world and society, so out of that came this sculpture-performative kind of work. It is like the scientist exploring alternative ideas—I wanted to be not necessarily something that is defined.”

— Nick Cave

Beverly Fishman

For over 25 years, Beverly Fishman has studied the science, imagery and advertising of the pharmaceutical industry. Within Fishman’s works, color and surface are calibrated for maximum effect, transforming the iconography of the pharmaceutical industry into hard-edged relief painting. The artist uses hue and texture to destabilize the viewer, with bright contrasts and slight shifts that cause varying levels of optic confusion and palpable disorientation. Fishman paints the edges of her works in bright fluorescents that leave a hovering glow on the gallery wall, a symptomatic and circumstantial buzz that radiates from each specimen. The artist appropriates pill forms that are at once familiar and addictive, thereby drawing from empirical research as well as the complex macro and microcosms of human cost. Full of emotion, the works “channel loss and joy,” forcing us to consider our own attraction, revulsion, and dependence.

“In my work, I hope the colors and forms—even if you know nothing about them—evoke a technologically mediated world, one in which our desires are fed by the mass media and our identities are influenced by the products that we consume.”

— Beverly Fishman

Loie Hollowell

Loie Hollowell is recognized for her paintings that evoke bodily landscapes and sacred iconography, using geometric shapes to move the body into abstraction. Originating in autobiography, her work explores themes of sexuality, often through allusions to the human form with an emphasis on women’s bodies. The artist’s early work shifted from abstraction and metaphor to figurative painting before introducing reflection and mirroring, which transformed it into the radiating symmetrical silhouettes she has come to be known for. Hollowell uses drawing as a point of departure, pushing personal or metaphorical depictions of the body into a lexicon of sacred shapes: mandorla (the sacred almond shape representing union); ogees (ancient serpentine-shaped architectural details); and lingams (the Hindu god Shiva as represented by a phallus). With strong colors, varied textures, and geometrical symmetry, Hollowell’s practice is situated in lineage with the work of Georgia O’Keeffe, Gulam Rasool Santosh, and Judy Chicago.

“Beauty for me is not just visual, it is also experiential. I want the viewer to come away not necessarily knowing what was trying to tell them about, say, my birth experience, but absorbing an impression of brightness or richness or radiance that has something to do with their relationship to their own body.”

— Loie Hollowell

Tony Matelli

Tony Matelli’s artistic practice contrasts the ancient and the topical, the classical and the common. Matelli describes his garden statues as modern-day memento mori - a still life that suggests transience and the decay that begins at the pinnacle of perfection. The degenerating human ideal in marble is set against the tantalizing richness of ripe fruit, a contradiction of culture versus nature as both decompose. The series was born one day when Matelli passed a scrapped car at a junkyard on the way to his studio; on a whim, he placed a strawberry he was carrying with him on the hood: “The two objects spoke to one another in a powerful way. It reminded me of those “Death and the Maiden” paintings from the Northern European Renaissance. It seemed somehow erotic and strange and spoke very clearly to me about youth and old age. I started developing the idea using statuary instead of other objects to more clearly implicate the viewer in the work.”

“They are decayed marble and concrete statues, which act as a support for fresh perishable food items that have been rendered out of bronze and other materials. They are frozen moments; they depict contrasts...”

— Tony Matelli

Josh Sperling

Josh Sperling employs the language of minimalist painting from the 1960s and 1970s, primarily working with shaped canvases. In their three-dimensionality, his works cloud the distinction between painting and sculpture, and he expertly crafts winding and layered organic shapes from rigid plywood before hand-stretching canvas over his elemental parts. Mining a wide range of sources, from design to art history, Sperling has crafted a unique visual vocabulary remarkable for its emphatic quality and boundless energy. For his bubble works, the artist employs an early trope and creates a link between them that becomes a building block: “Those were the results of taking that first shape - the bullseye - and having them morph into each other almost like two water droplets on the table when they start to connect. That shape has become an elemental brick and now I can keep on using it to realize these different overall shapes.”

“Frank Lloyd Wright has always been a hero of mine. His use of geometry continually inspires me. The opportunity to display my painting within his space is a dream come true.”

— Josh Sperling

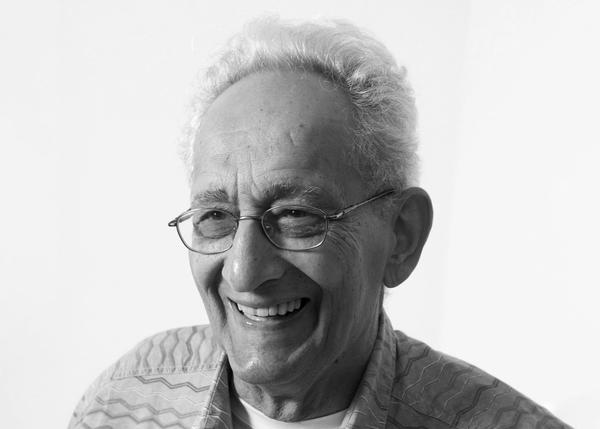

Frank Stella

An early adopter of 3d printing and digital modeling, Frank Stella’s recent work utilizes computer technologies to explore how subtle changes in scale, texture, color, and material can affect our perception and experience of an object. Where some have interpreted his expansion over the years as radical departures from his minimalist works and geometric canvases of the 1960s, the artist clarifies an ongoing exploration of symbols and ideas; Stella once shaped his canvases like stars and lattices and now, he is pushing that construction into the third dimension. Says Richard Klein, Director of Exhibitions at the Aldrich during a recent presentation of Stella’s stars over his career, “Even with something as stable and as knowable as the star, Stella is able to reinvent it every time he approaches it and make you look at it in a different way.”

“Stars are complicated but interesting shapes. They become even more interesting when exploring their relationship with other things.”

— Frank Stella

Hank Willis Thomas

Hank Willis Thomas is a conceptual artist focusing on themes relating to identity, commodity, media, and popular culture. His work often incorporates recognizable iconography from advertising and branding to explore the toxic generalizations that so many companies reinforce around race, gender, and ethnicity. Thomas created one of his most iconic photography series in 2006, titled B®anded, where he portrayed the marked bodies of Black men with the Nike swoosh logo, scarring their flesh and recalling the history of branding slaves in America, as well as the objectification of Black male bodies in contemporary culture. Thomas has explored this language of branding and advertising throughout much of his career. “I started thinking about logos as our generation’s hieroglyphs,” said Thomas in an interview with The Brooklyn Rail in 2015. “They can be embedded with so much meaning, and I really wanted to play off that.”

“I was really wanting to think about what it means to create monuments for people who aren’t seen as valuable or important or society.”

— Hank Willis Thomas

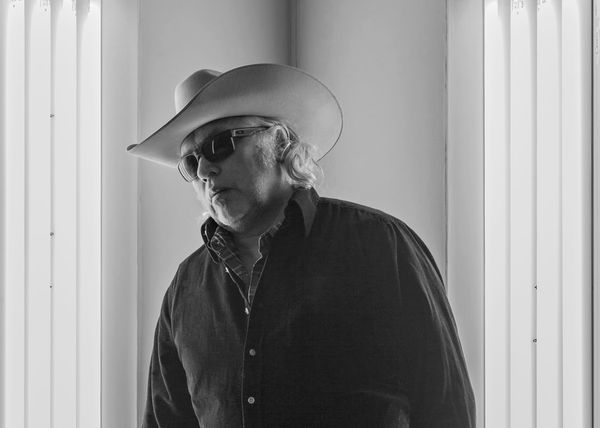

Blair Thurman

With influences ranging from Pop art and Minimalism to childhood relics, punk music, and 1970s cinema, Blair Thurman’s forms present a subconscious realm of abstract geometries that are unusual, personal, and accessible. The artist employs the transformation of recurring frameworks and forms pulled from slot-car racetracks, American vernacular, and found shapes from daily life to create a personal lexicon. Thurman refers to the immured style and significance of his work as its “signature-content” as he examines the memory and poetry that is innate to observation. According to artist Steven Parrino, Thurman is “a Pop-Sensitive… his method is gaze and memory rather than cold analysis. More like the free associations of a Beat poet on the road, happening upon Gonzo situations and structures, awash in neon… the dark self on the road to nowhere” (The Return of the Creature, the Künstlerhaus Palais Thurn und Taxis, Bregenz).

“I see it as associative abstraction; yes, it’s abstraction, but it’s not formal abstraction about color and shape, it actually is shapes that have associations. They make you think of things, they come from things.”

— Blair Thurman

Austyn Weiner

Following the recurring presence of figurativism in her work, painter Austyn Weiner has recently distilled her layered, turbulent forms further into abstraction. Using oil on canvas, the works remain attached to personal narrative but become more universal, opening themselves up for a multitude of readings where isolation, love, and chaos enter all of our lives. Weiner’s practice explores a duality of forces that are both persuasive and forlorn, exploring romance, rejection, loneliness, and performance. Built through a series of elongated processes and sudden gestures, Weiner teases notions of attraction and availability that cannot exist without the presence of fear. Her paintings are an exercise in the ongoing ritual of self-exploration, and communicate a particular vitality and conflict that is characteristic of youth; she is a painter and a personality whose lexicon is bound to grow and change while retaining its vulnerability.

“My work has always had a certain aesthetic approach dating back to my dark room experiments and my first self-portraits. I think I have always been drawn to a confident and seductive aesthetic across any medium I explore. It is more about the gesture, mood, and narrative and what it calls for. And in my case, a mix of hard and soft lines, expressive automatic gestures, and thoughtful, tender moments.”

— Austyn Weiner