Anatomy is a platform that dissects and narrows in on the various parts of an artist’s practice through the lens of their studio. This presentation provides a glimpse into an artist’s background and process through a multimedia tour including video, audio clips, imagery, and conversations with fellow artists, curators, and other figures who have been influential in shaping and understanding these creators and their works. Anatomy's intent is to examine the myriad of ways in which an artist finds inspiration, merges art and life, and is driven by experience and the people that come into their world. We hope that this look into the lifeblood of the artist’s practice will affect an even deeper reading of the works included and those yet to come.

Background

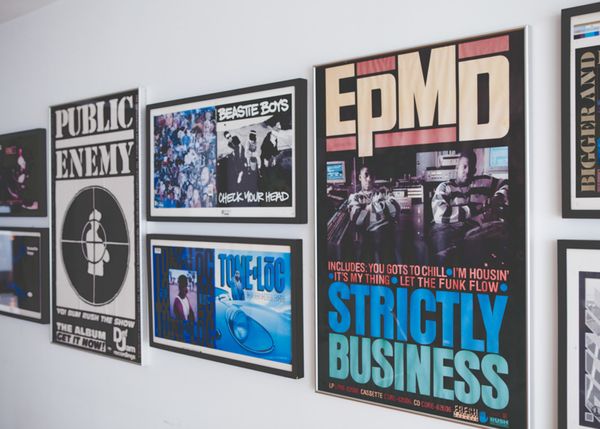

Born and bred in New York City, Haze has been influential in the worlds of graffiti, graphic design and contemporary art for over four decades. After making his initial mark as a pioneer of graffiti’s rise above ground in the 1970s and 80s, Haze made a career out of pushing creative boundaries in a number of mediums, soon emerging as the premier graphic designer of the exploding Hip Hop movement. Throughout the next decade, Haze created iconic logos, album covers and identities for the likes of The Beastie Boys, Tommy Boy, LL Cool J, EPMD, MTV, and many others. The new millennium has seen Haze make a serious commitment and return to painting and drawing. Working out of his studio in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, Haze’s personal work reflects an array of important movements in art history. Anatomy: Eric Haze presents 12 works that deal with abstract shapes and intersecting lines, reflecting universal themes and his passion for movement and gesture.

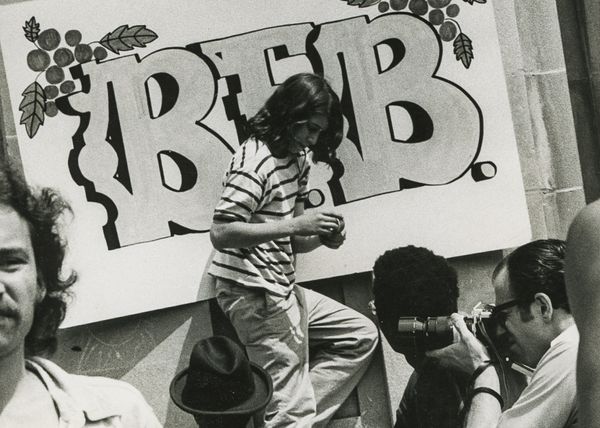

Haze pasting a hand-drawn backdrop he created for “Bethesda Fountain Band” in Central Park, 1974

Haze climbing the pipes of an abandoned train station on 91st Street and Broadway. Photo Matt Weber, 1973

Haze leaning against the Campbells Soup train painted by Fab 5 Freddie, 1979

Album covers and posters designed by Haze in his Brooklyn showroom, 2009

Coney Island MCA memorial mural by Eric Haze, with his 1968 Dodge Dart race car, 2016

Haze brand product showroom in Brooklyn, 2023

Inspiration

Haze’s interest in art began at an early age, when he and his younger sister were sitters for a 1971 portrait by Elaine De Kooning at just 10 years old. The painting was made in several afternoon sessions at De Kooning’s apartment near Union Square, fostering an experience that introduced to Haze the legacy of the Abstract Expressionists from which his practice today draws significant influence. Allowing instincts and emotions to guide his creative decisions, Haze follows in the footsteps of the movement’s leaders in these artists’ attempts to convey their inner experiences through their work, using painting as a means to reveal the subconscious and universal human condition. Color was viewed as one of the most powerful tools of communication, not merely used to depict objects in the world, but as a primary means of expression in its own right. To this end, Haze’s captivation with a black, white and gray color palette references Jackson Pollock’s black pourings—which resemble graphic design while embodying the synthesized essence of his renowned drip paintings—and Robert Motherwelll’s ‘Elegy to the Spanish Republic’ series, comprised of over 200 pieces in memoriam of the lives lost in Spanish Civil War, through which the late artist “discovered black as one of [his] subjects.”

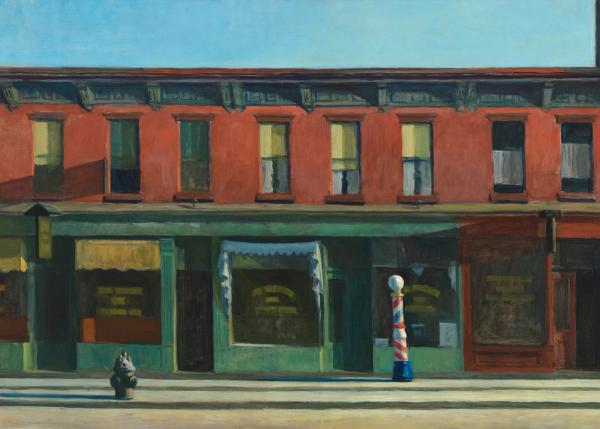

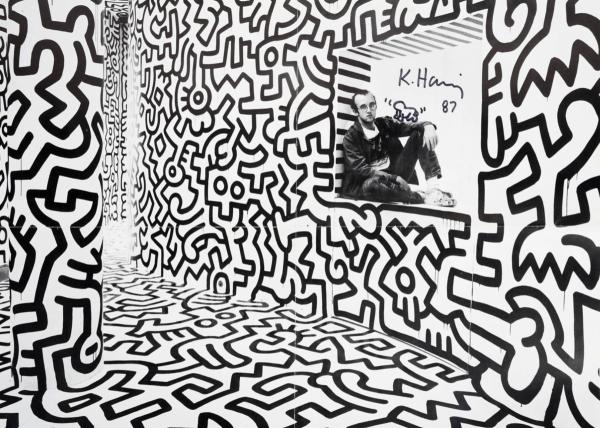

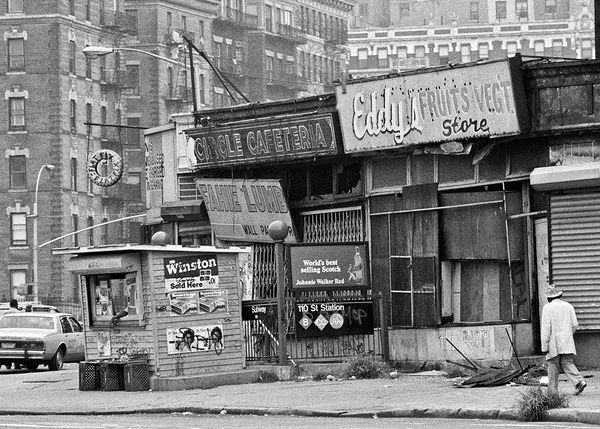

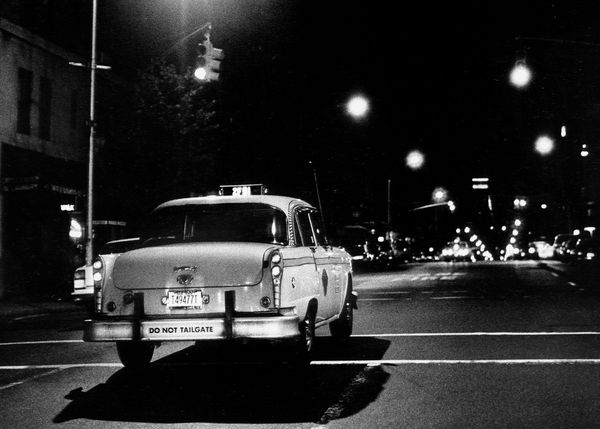

Haze's venture into portraiture reflects the fearlessness of his modern predecessors, and in a natural transition, begins through the study of his environment. In a personal reflection, Haze voices that “nothing is more a part of who [he is] and [his] experience [than New York City].” Haze’s teenage years were spent as a founding member of the influential graffiti collective The Soul Artists, with whom he first exhibited in 1974. He then went on to exhibit paintings and drawings alongside close friends such as Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring in the early 1980s; upon opening his SoHo Pop Shop in 1986, it was Haring who first encouraged Haze to create product. Observing first-hand Haring’s success in radically bridging the gap between the art world and the streets, Haze cites the celebrated artist as a steadfast muse. Haze’s creations today are very much rooted in these formative relationships and experiences, for example his urban landscapes, which draw their initial source from a combination of memory and existing imagery. In this regard, Haze derives inspiration from the photographs of prolific New York street photographer Matt Weber, a longtime friend who served as a mentor to Haze throughout his emergence as a graffiti artist, oftentimes documenting him in action. The works take shape through Haze’s impressions of the city and its evolution over the decades—he does not focus on its landmarks, but on the unassuming street corners and gritty alleyways in which he finds endless hidden beauty. Much like Edward Hopper’s exacting portraits of the twentieth-century metropolis, Haze’s scenes are often devoid of distinctive figures, emphasizing the anonymity and introspection found in a bustling urban center.

“One of the most important things to me about painting is to feel a personal connection and passion for the subject, whether it's a landscape or a person. And one of the things that was so obvious to me at the beginning of this arc, of this work, was that nothing captured my imagination more than New York City. ”

— Eric Haze

Detail of Carlo Carra, Horse and Rider, 1915

Edward Hopper, Early Sunday Morning, 1930

Keith Haring, Pop Shop, 1987

Robert Motherwell, Elegy to the Spanish Republic No. 79, 1962

SNAKE 1, 1973

Detail of Jackson Pollock, Autumn Rhythm, 1950

Matt Weber, Harlem, 1985

Matt Weber, Night Shift, 1989

Artwork

Working within the realm of figuration, Haze's ‘Night Moves’ and ‘De Kooning’ series, both executed in his signature gray-scale color palette to reflect an interest in architecture and design, honor the environment and people that have shaped the artist's identity, ultimately memorializing a small slice of collective consciousness through impressions of personal experience. Working in various styles from landscape to portraiture, Haze's practice is rooted in a deep passion for his subject, and echoes the prism of memory through an organic approach to linework.

The ‘Night Moves’ series designates Haze’s initial shift from typography and abstraction into figurative work. The paintings at times reveal elements of constructivism, geometric abstraction and conceptualism, balancing unique icons, abstract shapes and intersecting lines to achieve a distinct language, and served as a gateway into his first body of portraiture with the ‘De Kooning’ series. In 2020, Haze spent months as an artist-in-residence at the Elaine de Kooning House in East Hampton, New York. Inspired by De Kooning, Haze began working on his first-ever series of portraits, which take either the studio itself or the late artist’s paintings, including the 1971 portrait of him and his sister, as their subject matter.

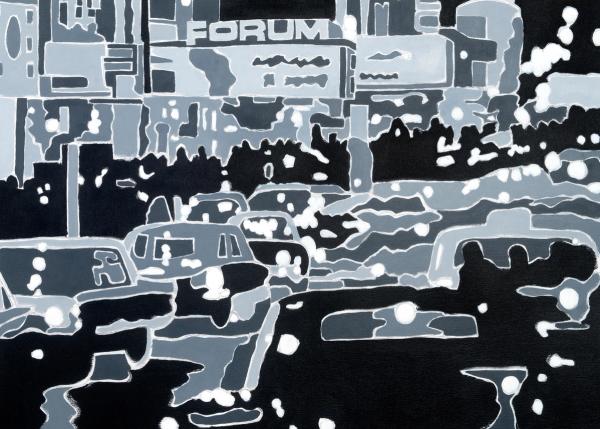

Belmore Cafe and Night Runner

Haze’s ‘Night Moves’ series possesses a cinematic quality, the artist citing documentaries, b-roll footage and, specifically, film noir—a classic film genre that rose in popularity in the 1950s as anxieties of the postwar era provided fertile ground for exploring darker and more introspective themes amid civilians—to be key sources of inspiration in both the paintings’ aesthetic and thematic elements. Created in 2019, Belmore Cafe and Night Runner are amongst the first urban landscapes Haze ever produced, and his formal approach to the canvas, mainly his use of black and attention to greater expanses of space, evokes a ghostly aura. The reductionist works nostalgically capture a bygone era of New York, presenting the city not as it is today, but as Haze remembers it; boxy cars and vintage signage serve as pronounced time markers, uniquely transporting viewers to a preserved period in time. Night Runner is a rare constituent in the ‘Night Moves’ series in that its composition centralizes a distinguishable figure, however, the figure’s solitariness aids in emphasizing the intended sense of atmospheric vacancy.

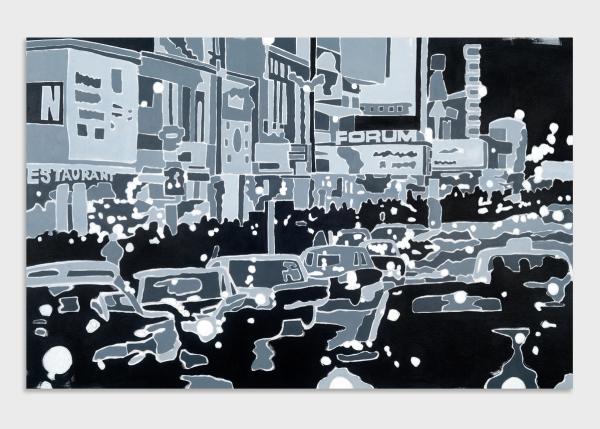

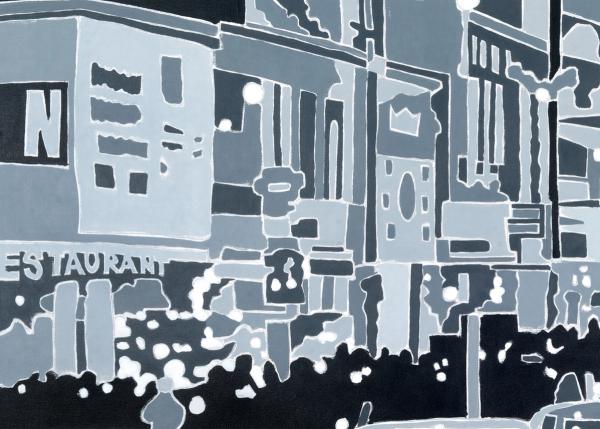

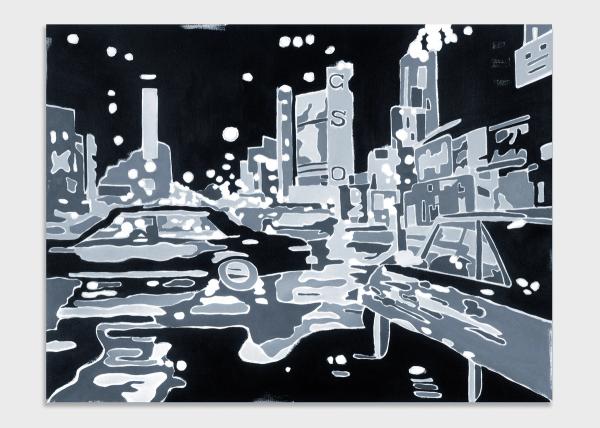

Electric City

Eric Haze

Electric City, 2023

Acrylic on canvas

42h x 66w in

Created in 2023, Electric City illustrates the evolution in Haze’s painterly craft. As he becomes increasingly acquainted with his material, the landscapes inherently grow to become much more complex. Tones of color are expanded and forms become less discernible, and in turn, once eerie scenes have transformed into lively cityscapes emanating with action. Haze’s skilled method of documenting his environment goes beyond the mere portrayal of its true physical qualities. Rather, he places a primary focus on channeling the subjective energy that animates his surroundings to capture the atmosphere’s vital essence. By distancing himself from a realist approach to his source, Haze succeeds in pushing recognizable urban features, such as bright lights, puddles and crowds of pedestrians, into a blur of abstraction.

Details of Electric City, 2023

Acrylic on canvas

42h x 66w in

Listen to Haze reflect on this series

0:00 |

Street Dreams

Eric Haze

Street Dreams, 2023

Acrylic on canvas

42h x 56w in

An integral element of both graffiti and graphic design, accessibility has long been a fundamental driver of Haze’s creative pursuits. Upon shifting his focus to the ever-exclusive world of fine art in recent years, he found the territory to uphold this core value in his chosen subjects and their deliberate presentations. Exemplified in Street Dreams, Haze’s stylistic approach to his paintings works as an agent in affecting nostalgia, memory and reflection. He distills scenes down to their most basic visual indicators to allude to a dreamlike state. Imaginative, fragmented and oftentimes nonsensical, these qualities of the dreamplace are reflected in the soft edges of his forms, or the occasional sighting of an unfinished brushstroke. In working to capture fleeting sentiments of his own recollection, Haze creates a greater space for the viewer to draw their own associations to the scene, fostering a collective consciousness that transcends the painting’s pointed origin.

Crossroads and Studio Interior with Ladder

When delving into the unfamiliar realm of portraiture during a residency in Elaine De Kooning’s East Hampton home in 2020, it was Haze’s natural instinct to approach the art form through the lens of his environment, exploring De Kooning’s studio in all its spatial dynamics. It was there in her East Hampton studio, built by the artist it in 1978, that De Kooning spent the rest of her career working, creating some of her most recognizable and monumental paintings, including the series Cave Walls and Cave Paintings (1985–88), inspired by a trip to Lascaux, France.

Cross Roads and Studio Interior with Ladder speak to Haze’s early interest in architecture, as well as his natural inclination to capture the spirit of humans through inanimate objects. De Kooning’s studio ladder, for example, is an artifact studied in many of Haze's portraits that symbolizes the reigning presence of De Kooning's effervescent soul in the spaces she once occupied. When examining the two works side by side, one can immediately recognize shared distinctive qualities that prevail across Haze’s disparate bodies of work, including rigid linework, subjective perspectives and, notably, a neglect of color, which can be accredited to a number of different grounds. His devout use of gray tones reflects his early career; coming up as a graphic designer during a period of time when color was not readily available due to technological limitations, Haze learned to visualize his ideas in black and white. As a result, he adopted the belief that if an artist can create a work of art that is successful and dynamic in black and white, and does not depend on the subjectivity of color, they can create anything. An innate opposition to color as an avenue of expression further lends to his interest in line and form existing as their own result.

“I consider the interior paintings the most graphic and true to my original wheelhouse. It was the first series I completed before moving on to the more figurative portraiture. ”

— Eric Haze

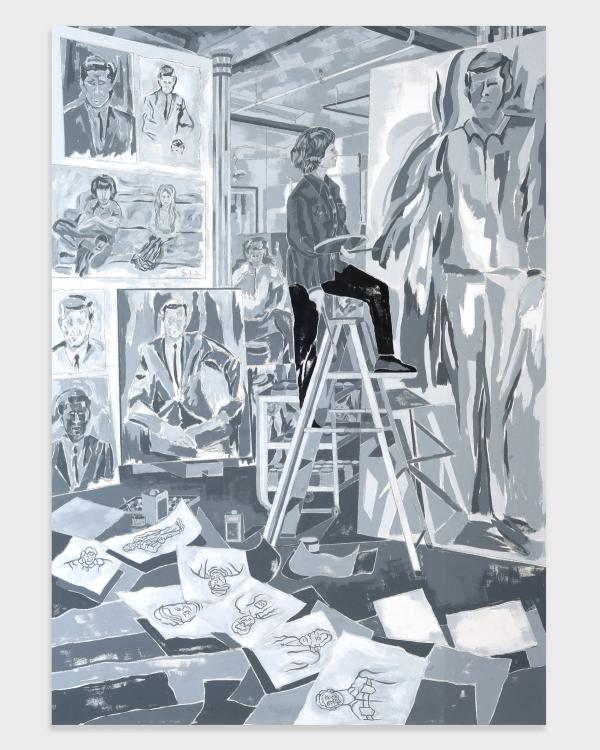

Elaine at Work / Union Square Studio

Eric Haze

Elaine at Work / Union Square Studio, 2020

Acrylic on canvas

90h x 69w in

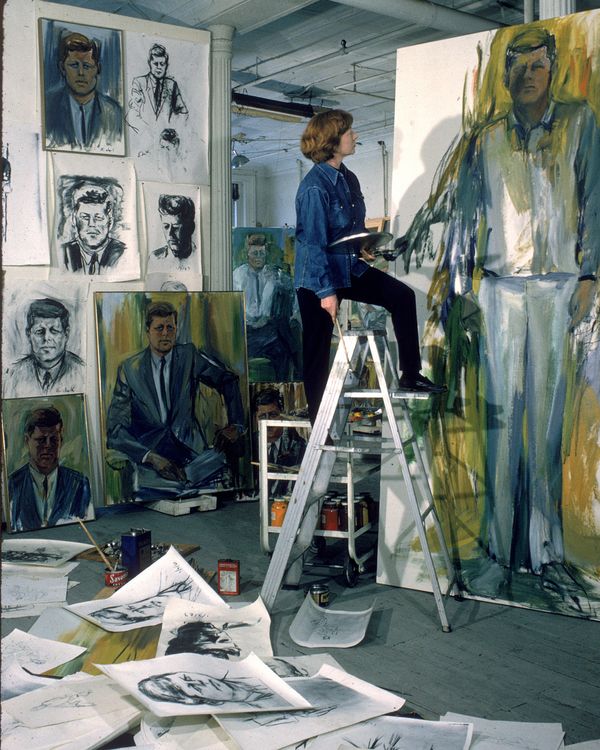

A modern rendition of a 1963 photograph by Alfred Eisenstaedt capturing Elaine De Kooning at work, Elaine at Work / Union Square Studio is the largest and final painting that Haze created at his residency, and serves to honor De Kooning’s prolific legacy and mentorship. Haze alters a number of the photo’s original contents within the frame, including a pair of portraits of John F. Kennedy installed left of De Kooning, which he replaced with the painting of him and his sister. Its horizontal composition illustrates Haze perched on a couch, arms and legs crossed, with his sister positioned beside him, hands resting in her lap. Further, swept across the studio ground, Haze substitutes a number of drawings that were originally studies of JFK with his own sketches of friends and contemporaries in a generational weave of past and present.

When a young Haze would break from his sitting sessions at the Union Square studio, De Kooning encouraged him to experiment with her oil paints. The juvenile works he produced served as his true introduction to art in the context of the creator, a position that unbeknownst to him would constitute his future ahead. Fast forward to today, the residency and ‘De Kooning’ series foremost facilitated an introspective, emotional dive into the dynamic constructs of Haze’s identity. Under De Kooning’s spiritual guidance, Haze channels his younger self in a reflection of his life’s trajectory had graffiti not entered the picture in his early teenage years. Embracing the lexicon of history unveiled in his formal exposure to and studies of the Abstract Expressionist masters, Haze unearths a dormant facet of himself that had remained undiscovered until this moment. Namely, the works have opened up a new field of vision for Haze that points inward rather than out.

Elaine De Kooning made dozens of drawings, sketches and paintings of John F. Kennedy in 1963. Photo by Alfred Eisenstaedt.

Listen to Haze reflect on this painting

0:00 |

Self Portrait with Piano and Self Portrait with Bus

Self Portrait with Piano and Self Portrait with Bus pose Haze at two different stages in his life, and when analyzed side by side, stand to represent the defining experiences within the temporal and metaphorical space that bridges them. Upon initial observation, the viewer’s attention is captivated by perceptible contrasts between the boy and the man, mainly in their physical attributes and attire. Positioned in the left canvas, Haze with a long head of hair sports a classic three-piece suit, while in the right canvas, he is rendered clad in an oversized t-shirt and black pants. The latter ensemble, which has become emblematic of Haze’s daily uniform, exemplifies the style synonymous with his streetwear brand HAZE—established in 1991, it was one of the first to emerge from the Hip Hop era. Nevertheless, there is a persistence in the figures’ postures, each leaning to their right to symbolize their one nature.

Conceptually, Self Portrait with Piano and Self Portrait with Bus are akin to the ‘Night Moves’ series in the introspective approach Haze takes to them. Incorporating elements of his abstract works into the paintings’ backgrounds, he signals a visual portal into the landscape of his mind rather than pushing a spatial context. Further, the stylistic decision frees the figures from limits of time, acknowledging the ever-changing nature of humans and the world. While with his painting practice Haze is exceedingly concerned with exploring external subjects and shared existences, these self-portraits serve as a reminder of the deeply personal origins of his work.

Portrait Studies

Graphite studies play a preliminary role in the production of Haze’s final pieces, such as the two pictured above of José Parlá and Brian Donnelly (KAWS), which are referenced in Elaine at Work / Union Square Studio along with sketches of Lenny McGurr (Futura), Lee Quiñones, Doze Green and Todd James. Exemplified by these noteworthy drawings, Haze often references his contemporaries—the people who he came of age with, who have inspired and shaped his identity and creative pursuits since the start—as an access point into modern art’s historical arc. As pioneers in elevating graffiti art into the mainstream, Haze and his comrades had no predecessors to look up to for guidance; thus, they relied on each other for direction in their communal navigation of uncharted territory. In watching his many peers of homogenous origin develop distinguished voices in the world of fine art, Haze has found the power to embrace the cross-section of what defines design and graffiti, and the confidence to establish a vision that is uniquely his own.

“[My peers and I] were confronted with a bunch of unfamiliar choices and challenges in terms of how to establish value, how to translate these identities that were uniquely personal into something that became more universal and created [meaning] in the world. ”

— Eric Haze

Elaine with Cigarette

Eric Haze

Elaine with Cigarette, 2020

Acrylic on canvas

42h x 42w in

Elaine with Cigarette is based on a 1980 black and white photograph by Timothy-Greenfield Sanders—a quintessential shot of the artist with her ubiquitous cigarette in hand. The painting exhibits a more intimate interaction between Haze and his subject, and, one of the final portraits he created at the residency, embodies an achieved conviction in his craft—particularly in the defining of facial features such as eyes, mouths, noses. Historically, the skills required to perform the breadth of Haze’s artistic undertakings have manifested themselves rather instinctively; contrarily, figuration and portraiture validated the least natural, most daunting challenge he recalls to have faced. For Haze, a vital draw to De Kooning as such a prominent inspiration was her fearless brush, known to race across her canvases in decisive, athletic strokes. It is this essence that Haze not only aims to conquer in the subject’s depiction, but within himself, too. Once judicious with the color black out of initial intimidation, his notable use of the hue in the painting’s background is a visual statement considered to be his greatest display of confidence.

Eric Haze

Elaine with Cigarette, 2020

Acrylic on canvas

42h x 42w in

Listen to Haze reflect on this painting

0:00 |

Conversations

Sean Corcoran, Curator

Sean Corcoran is the Curator of Prints and Photographs at the Museum of the City of New York. His exhibitions explore the visual landscape of the city and its inhabitants, and have included City as Canvas: Graffiti Art from the Martin Wong Collection, Through a Different Lens: Stanley Kubrick Photographs, and currently on view New York Now: Home - A Photography Triennial. He has written extensively on photography, graffiti and street art. Both longtime observers and chroniclers of New York City and its surrounding boroughs, Corcoran and Haze discuss Haze’s origin story and early graffiti days, as well as the shifts in his painting style as a result of his personal growth and perceptions of the world in his later age.

Photo by Robert Herman

“The way [Haze] paints is not overly detailed. It is almost like [his] own memory is on the wall. It's not photographic realism—it's the way [he's] recalling [these scenes] in [his] mind.”

— Sean Corcoran

Sam Friedman, Artist

Sam Friedman’s work is rooted in the tradition of American Abstract Expressionist painters who explored line, color, and the systematic application of paint. Within this heritage, Friedman examines methodical processes where repetition and self imposed parameters lay the groundwork for his compositions, but permit him the freedom to build each piece instinctively by hand. The two painters engage in a cross-generational dialog that considers Haze’s interest in communicating with a broader audience through a populist means of distribution and how this concept translates into his contemporary practice, as well as the changing relationship of art, design and fashion over the years. A former studio manager of Brian Donnelly's (KAWS), Friedman reflects on the influence that Haze’s generation of role models has had on his own artistic pursuits.

“These paintings come full circle in the sense that they create a new form of regionalism, then build upon the already existent history of the subject, all through the iconic 'Haze' qualities that are built into the muscle memory of [his] hand.”

— Sam Friedman

Barry Schwabsky, Art Critic and Historian

Barry Schwabsky is art critic for The Nation and co-editor of international reviews for Artforum. His recent books include The Perpetual Guest: Art in the Unfinished Present (Verso, 2016) and The Observer Effect: On Contemporary Painting (Sternberg Press, 2019) as well as two books of poetry, Feelings of And (Black Square Editions, 2022) and Water from Another Source (Spuyten Duyvil, 2023). The critic and artist discuss Haze’s painting practice within the greater context of modern art’s history, and Schwabsky ponders Haze’s seemingly austere use of color in its ability to unite his disparate bodies of work. Building off of Haze’s interest in studying his peers and predecessors, the conversation further explores how moments of isolation dissonantly fuel communal narratives.

“When I see these paintings, I see [Haze] reconnecting with a deeper history [of modernism and abstract painting] that goes back before [his] lifetime.”

— Barry Schwabsky

Studio Visit

READING LIST

The Faith Of Graffiti by Norman Mailer, The Power Broker by Robert A. Caro, Pimp by Iceberg Slim, Waiting For Godot by Samuel Beckett, The Hillaker Curse by James Elroy, The Fountainhead by Ayn Rand, From Bauhaus to Our House by Tom Wolfe, The Godfather by Mario Puzo, Krazy Kat Anthology by George Harriman, and 9th Street Women by Mary Gabriel.

“There were a lot of early influences from rock and roll to modern art that didn't really play out in my experience and career with graffiti and design. But they're coming very much back into focus now.”

— Eric Haze