Anatomy is a platform that dissects and narrows in on the various parts of an artist’s practice through the lens of their studio. This presentation provides a glimpse into an artist’s background and process through a multimedia tour including video, audio clips, imagery, and conversations with fellow artists, curators, and other figures who have been influential in shaping and understanding these creators and their works. Anatomy's intent is to examine the myriad of ways in which an artist finds inspiration, merges art and life, and is driven by experience and the people that come into their world. We hope that this glimpse into the lifeblood of the artist’s practice will affect an even deeper reading of the works included and those yet to come.

Background

Anatomy: G.E. Liu features nine works by the Taiwan and Detroit-based artist, whose multiform paintings on silk are rooted in ancient Chinese alchemy and Jung’s concept of the hero’s journey toward individuation. Her visual vocabulary explores the commonalities and variations between the East and West and infuses humor, sexuality, and self-deprecation. Liu is fascinated by the body-spirit cultivation of Medieval Chinese science and cosmology and sees herself as something of an alchemist as she mixes and contrasts ideas around mythology, gender, love, theology, and cultural identity. “My practice focuses on building a mythological world as a coded satire of reality. As both Christianity and consumerism are the largest influence of western culture's invasion in Taiwan, I celebrate them just like I embrace the celebration of love, worship, apocalypse, social media, and Taiwanese local culture. My intention is to explore the psychological realm of what lies beneath the mythological alchemic superstructure through my own intuitive visual language.”

Inspiration

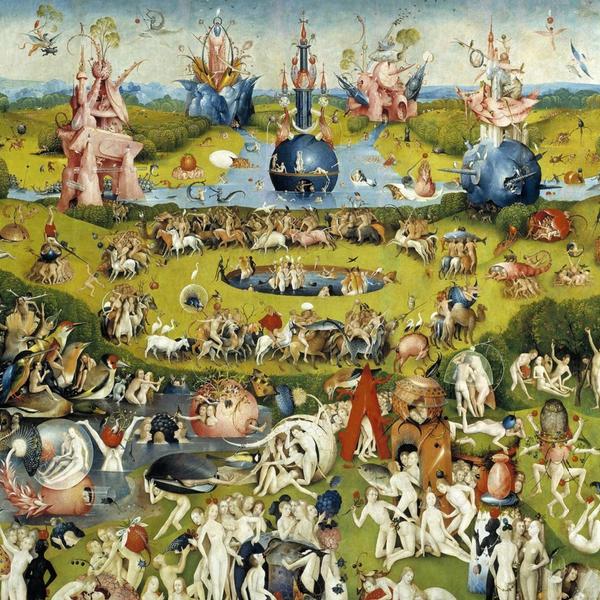

Hieronymus Bosch

The Garden of Earthly Delights, 1490-1500

Liu’s work is inspired by imagery and concepts followed over a long tradition of art in both Asia and in the West, where artworks born from theology and morality present allegory, conflicts of good vs. evil, and illustrations of the rewards and punishments inflicted on mortals as they act in alliance or defiance of religious teaching. Of the earliest materials that have influenced Liu are Tibetan Thangkas, which are fragile Buddhist paintings (often on silk) that can be rolled up for safekeeping or hung on the wall during meditation ceremonies. Often woven, embroidered, or appliquéd, thangkas feature peaceful and wrathful deities as well as mandalas, and Liu has long admired their composition and sense of space. Another strong influence is the work of Northern Renaissance painter Hieronymus Bosch, whose most famous work, The Garden of Earthly Delights, is a humorous, macabre and absurdist depiction of the ‘benefits and hazards’ of marriage through the lens of biblical storytelling. The triptych presents Adam and Eve in a harmonious landscape on the left panel, a hedonistic paradise in the center, and a blazing hellscape awaiting them on the right. It is speculated that Bosch witnessed as a child a fire that engulfed his hometown (Hertogenbosch, 1463), and that the experience may have incited his desire to create nightmarish religious scenery later in life. An outsider artist of legend, the work of Henry Darger has also been inspirational to Liu. Reclusive and self-taught, Darger painted by day in his Chicago apartment above the school where he worked as a janitor at night; with no friends or family, his work went unseen until his death in 1973. For nearly 40 years, he worked on a 15,000-page story (known for short as ‘In the Realms of the Unreal’) that told the tale of 7 young sisters called the Vivian Girls. The girls were the princesses of Abbieannia, a Christian land, and led a revolt against child slavery that was imposed on their world by monsters and other sinister forces. Among other influences in Liu’s work are Frida Kahlo, William Blake, films ‘Holy Mountain’ and ‘Teeth’; and contemporary artists Inka Essenhigh, Hiba Schahbaz, and Korakrit Arunanondchai.

“I use silk—a traditional Eastern fabric—not only as a representation of my heritage but also within a post-colonial and global point of view. This contradiction within the material makes me think of many different aspects of our lives that may change over time. It's about being flexible. Just like the William Blake poem “The Marriage of Heaven and Hell,”— he talked about bringing the reason of heaven and the energy of hell together to create a tremendous power of creativity.”

— G.E. Liu

Again running from forest flame, 1910-1970

Plate from The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, 1793

Still from The Holy Mountain, 1973

Artwork

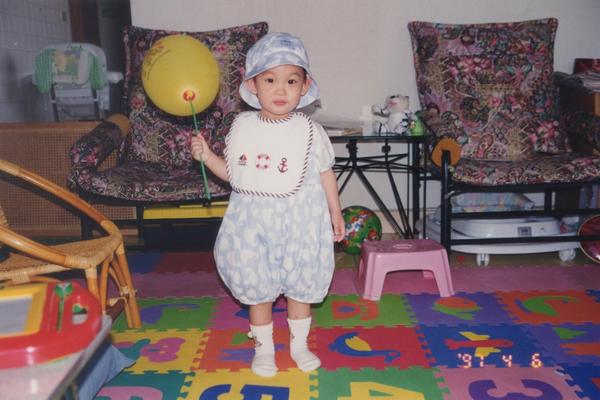

Liu was born and raised in Taiwan and traveled to the United States for her graduate studies at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan. It was during her time in the US that she first became acutely aware of the many parallels and distinctions that exist between Eastern and Western cultures, and began to look to these contradictions to guide the narratives and materials of her work. Liu develops female characters to act as heroines, villains, and innocents as they traverse her densely layered narratives. More often than not, these characters are the mortal receivers of lessons from the gods, objects of their affections, and at times, even subjects of their deceit. For Liu, it is important to present women in all their complexity, as they absorb judgment and expectation and transform it into life force: “I have a lot of female figures that are associated with snakes and dragons, or having a snake body eating its tail. The Ouroboros talks about self-destruction and rebirth simultaneously and to me, this aligns with how women and their bodies can be viewed as a double-edged sword, bringing power but also disgrace, love but also hatred.” The use of coded satire, romantic irony, and grotesque fantasy lightens the conceptual weight of the works, and the use of silk as a painting support does the same for Liu’s aesthetic. Silk has a long history as a reverent material in the East, but the West’s consumerist invasion has redefined it through mass production, deeming it kitsch. Another connection to Liu’s Taiwanese heritage is the use of color-changing lights, which represent Taiwan’s position as the global leader in LED manufacturing and remind her of night markets and religious decoration.

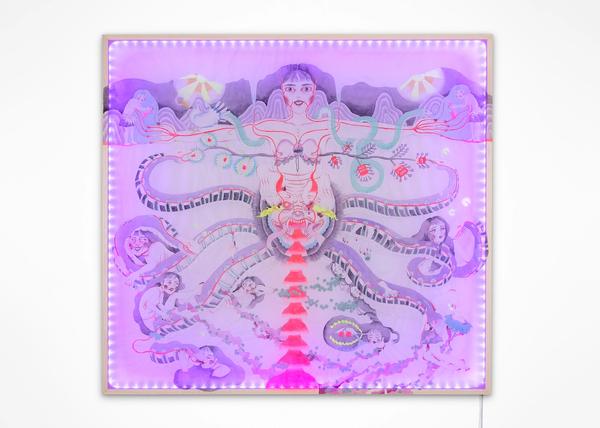

Promising Young Woman

Promising Young Woman, 2022

Gouache and watercolor on silk and adjustable color LED lights

48.5h x 52.125w in

Promising Young Woman began with ideas centered on the COVID vaccination. Liu found inspiration in the mRNA vaccine and how the DNA of COVID’s spikes was inserted into individuals’ bodies. The process of vaccination reminded her of how traumatic events have lasting impacts on people, resulting in either strengthened individuals or ruined lives. Throughout the continued development of the visual language on the surface of the silk, Liu began to recognize connections within multiple concepts.

The figure represents a young woman with fluorescent red lines throughout her body, that can be understood as blood or vaccine. The beast is representative of her vagina, which, along with the six snakeheads, is understood as the beast of the apocalypse. Liu is commenting on the controversy of how imagery and ideology shift between cultures, specifically how the vagina may be perceived as either evil or good. The painting horizontally mirrors itself, yet with close examination, it is revealed that each side represents a different narrative. As location continues to impact Liu’s work, the art-deco design of the Guardian Building is featured in Promising Young Woman within the skin of the six snakes. While the left side of the work depicts human girls successfully defeating the snakes, the right side portrays human girls being eaten by them. The figure is facing and battling her feminine nature within a misogynistic world.

Guideline of Five Essential Virtues for Promising Young Women

Guideline of Five Essential Virtues for Promising Young Women combines visual elements of Western alchemy and Detroit’s Art Deco infrastructure with concepts surrounding Chinese virtue and female virginity. The painting places special focus on Eastern culture, showcasing a group of mandarin characters pertaining to the five virtues by the Analects of Confucius: 溫 良 恭 儉 讓 (pronounced as wen, liang, gong, jian, rang). Together, they essentially translate to mean that a person is best to be modest and adopt mild reformism rather than using force in a revolutionary struggle. A primary inspiration for the painting, Liu pulled the same phrase from the Taiwanese novel "Fang Si-Chi's First Love Paradise," which tells the story of a 13-year-old Taiwanese girl who is groomed by her Chinese literature professor and after school tutor, the exploitative relationship resulting in the growth of severe mental illness in the teen. The novel is allegedly an autobiography—the author Lin Yi-Han tragically took her own life shortly after she released the book in 2017. This story represents the corruption that exists within Taiwan’s educational system (and those within other parts of Asia) in regard to power imbalances in an openly misogynistic culture. Guideline of Five Essential Virtues for Promising Young Women employs a cheerful, fairytale-like color palette that resonates with the vibrancy of a teenage girl, while the content, such as a virgin reposed in her own blood, is disturbing and subtle.

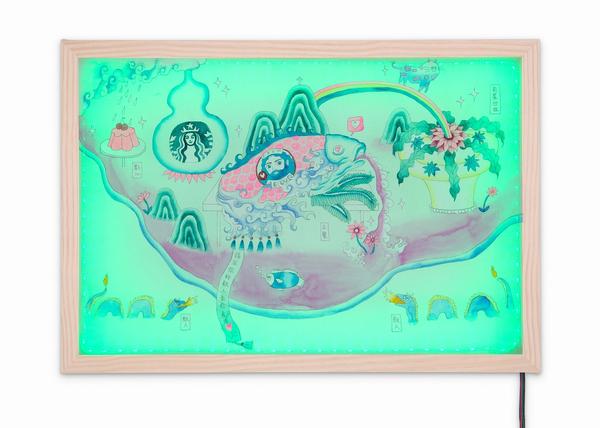

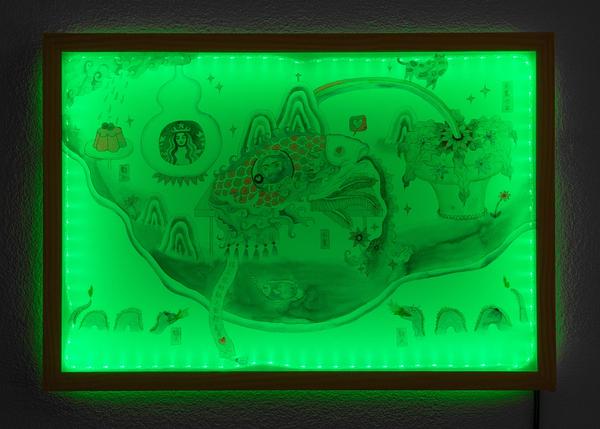

Virgin Wizard's Michigan Internal Alchemy

Virgin Wizard’s Michigan Internal Alchemy is a landscape, a map, and anatomy, simultaneously, focusing on Liu’s research of female virginity and Christianity. A virgin wizard is an aspect of contemporary culture that satirically refers to people who remain virgins into their twenties and are believed to be saving their virginity to gain superpowers. This urban mythology originates in the Japanese manga series Dosuperado by Owada Hideki. In the story, if one is a virgin at 20 years old, they are qualified to be an intern wizard, at 25 they qualify as a formal wizard, and at 30, a level-up wizard, etc. In the original manga, all of the virgin wizards are male and women are demonized as sexy women trying to take the virginity of the men for entertainment. A virgin male being laughed at and called a wizard is a cultural phenomenon throughout Japan; however, in Liu’s community in Taiwan, women have adopted this urban mythology, referring to themselves as virgin wizards as well.

Liu’s practice is intensely impacted by her surroundings. While living in Michigan, she developed a mythological space that included all of the locations she’s lived in. She recreated the settings by using the Chinese internal alchemy theory and borrowing one of the internal alchemy drawing structures. Because of Michigan’s common representation as a mitten, Liu relates the geographical imagery of the state to the human hand, and further, to the traditional form of Chinese medicine known as acupuncture. Similar to acupuncture’s focus on energy, Liu highlights the two most prominent spaces she spent time in while in Michigan— the Detroit area, which is represented by the spine, and Bloomfield Hills, represented by the stomach.

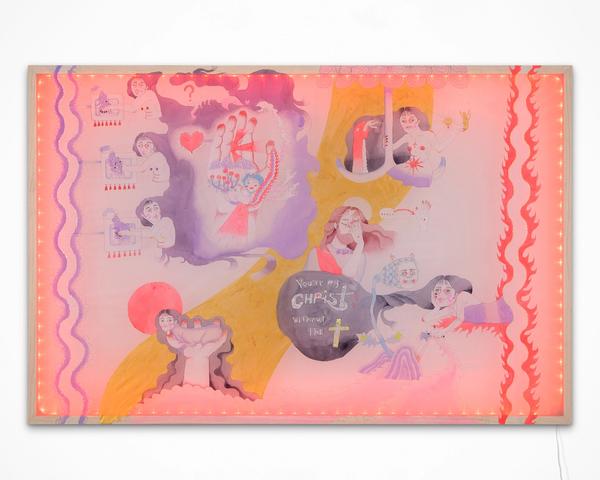

Poetic Hair

Poetic Hair, 2022

Gouache and watercolor on silk and adjustable color LED lights

32.75h x 50w in

Poetic Hair is inspired by Western ancient alchemy compositions, pop culture, and art deco elements of Detroit buildings, among other concepts. Similar to many of Liu’s works, there are many symbols within the piece, such as a common thread of images and text contained within the hair of female figures. This imagery relates to the idea that hair is an extension of wisdom because of its connection to and outgrowth from the tops of our heads. However, in the painting, Liu includes comedic aspects into some of the hair bubbles, referring to how wisdom and ignorance are often intertwined. One of the thinking bubbles contains a symbol of Michigan, the hand. There is a spine drawing on the right side of the hand. It is visually similar to the combination of the pillar of clouds and pillar of fire that flank either side of the painting. The smoke protruding from the spine and farming imagery on the left of the hand reflect the influence of the Michigan mural in the Detroit Guardian Building, painted by Ezra Winter. In the mural, Detroit is indicated as ‘manufacturer’, and West Michigan is referred to as ‘agriculture’. Further symbolism includes the pillars of clouds and fire, which reflect verses from the book of Exodus in the Bible; and the double hooked/seated umbrella, which relates to children’s culture in Taiwan and Japan where children write names under each side of an umbrella as indicative of secret crushes.

Poetic Hair, 2022

Gouache and watercolor on silk and adjustable color LED lights

32.75h x 50w in

Listen to Liu reflect on this painting

0:00 |

Happy Meal

Happy Meal, 2022

Gouache and watercolor on silk and adjustable color LED lights

48h x 62.75w in

Growing up, Liu considered a McDonald’s Happy Meal to be wholesome and sweet, containing just the right amount of everything a child needs: perfect portions of food and a toy that is carefully chosen for the narrative that the characters represent. Liu’s work aligns with this sentiment because many of the objects and creatures within her paintings are similarly depicted and possess personal narratives. The title is also a representation of nostalgia for Liu. As a child, her mom would convince her children to attend church regularly by offering a reward of Happy Meals after service. As such, Happy Meal contains references to Christianity, adding irony and humor to the work. The visual and conceptual complexity of the work is rendered through the narratives of the figures ebbing and flowing throughout the silk. The central figure is a white, blond Jesus within a ‘table’ shaped like an inverted ancient Dutch representation of the city of Tainan, Taiwan, Liu’s hometown. The map is from the 1600s when Taiwan was under colonial rule of the Dutch and Tainan was named the capital of Taiwan. She is questioning the continued impact of European colonialism and how globalization has affected Taiwan, with a particular focus on Christianity.

Details of Happy Meal, 2022

Gouache and watercolor on silk and adjustable color LED lights

48h x 62.75w in

Listen to Liu reflect on this painting

0:00 |

Take Me to Church

Take Me to Church, 2021

Gouache and watercolor on silk and adjustable color LED lights

14.75h x 20.75w in

Like the popular song by Hozier, Take Me to Church reflects on the feeling that many young people within religious groups experience in failing to meet the strict expectations of their community. What might be considered normal aspects of growing up and coming of age—such as experimentation, exploration, and self-expression—are often stigmatized within religious groups. Liu herself has experienced this treatment firsthand and says, “Having a dark side of religion is inevitable. Ultimately, human beings are in charge of institutionalized faith, and we are far from perfect. My relationship with faith is very complex; on one hand, it has helped me to become a better person, but on the other hand, I often see it used as a weapon.” The painting shows a figure holding a Jesus mask in front of their face as they place Oni emoji masks on another as a target. The figure pushes a lever to lower the masks—imagery that calls to mind a ‘Wizard of Oz’-like man behind the curtain—and the end of the mechanics reveals the barrel of a gun. ‘Oni’ means ghost in Japanese, and the mask is a symbol that signifies a belief in the battle between good and evil, acting as protection for the believer.

A Three-Course Dinner in Front of My Enemies

A Three-Course Dinner in Front of My Enemies, 2021

Gouache, watercolor and glitter on silk and adjustable color LED lights

14h x 20.25w in

As with Happy Meal, Liu references the Biblical verse of Psalm 23 in A Three-Course Dinner in Front of My Enemies which says “You prepare a table for me in the presence of my enemies." She finds this text particularly interesting, both because of the imagery it encourages—a feast prepared just for you as you sit across from your bullies and nemeses—but also because of the multiple interpretations it invites. To Liu, these so-called ‘enemies’ aren’t necessarily of the human kind, and feels that the verse could be just as easily interpreted to reference the things that hold us back: our insecurities, anxieties, and fears, or the voice that tells us we’re not good enough. The composition echoes Happy Meal, subtly revealing a map of Western Taiwan where dragons swim across the strait.

A Three-Course Dinner in Front of My Enemies, 2021

Gouache, watercolor and glitter on silk and adjustable color LED lights

14h x 20.25w in

Listen to Liu reflect on this painting

0:00 |

COVID-19 Good Luck Charm / Drug Bag

According to Chinese philosophy, the proper placement of good luck charms in the home is important for abundance and prosperity. There are many different objects and images that can be used as good luck charms, but popular choices include horseshoes, the laughing buddha, lucky bamboo, double happiness symbols, and custom charms that are created for specific wants and needs. Here, Liu has created her own COVID-19 Good Luck Charm / Drug Bags to ward off the pandemic; at the top of each piece are two antivirus symbols, and the figures use Christian crosses on sheilds and bikini tops. This melding of Chinese philosophy regarding luck with Christian faith imagery is an interesting and unlikely combination, as Christianity disregards the concept of luck and believes that everything in life follows God’s pre-ordained plan. This contrast of opposing beliefs—strongly Eastern and Western at once—lies at the heart of both Liu and her artistic practice. Another interesting aspect of these small works is their likeness to Chinese medicine bags, which are used to hold herbs and can be placed on the body to target specific ailments through external application therapy. This practice—as well as the placement of good luck charms—is an ancient discipline that has been used in China for centuries.

Conversations

Michael Xufu Huang, X Museum founder

Michael Xufu Huang is a Chinese art collector and curator, as well as the founder of the X Museum in Beijing. With Hunag and Liu’s shared experience of growing up in Asia and later attending school in the U.S., they discuss differences observed in the educational systems between the East and the West, along with contrasts amid the regions’ respective art markets. The pair agrees that a big draw for them both was the encouragement of creative freedom they found to be utterly prevalent in the States. Other topics of conversation include technology’s influence on art—from making art, to selling it, to experiencing it—and their mutual love for fashion, which is readily apparent in Liu’s work through her common yet subtle inclusion of designer brand logos.

“I do see a lot of younger, emerging artists, especially of Chinese descent, that use this new ink idea—this kind of ink and silk drawing—but I think the neon [LED lights] really distinguish [G.E.] from the rest… I think neon itself represents [this] age of how technology is so a part of our life. [Nowadays,] we need to use light and color to draw people’s attention.”

— Michael Xufu Huang

Inka Essenhigh, Artist

Inka Essenhigh is an American artist renowned for her dreamlike paintings, which translate her encounters with, and intuitions about, contemporary society into haunting, playful, sometimes disturbing visual scenes. Situated in their studios, the two painters meet over zoom, where they exchange insight into their personal creative processes, discussing various components such as inspiration, preparatory customs, choice in material, and more. The conversation carries on to consider how the artists’ works reflect the physical environments in which they are created, Essenhigh calling attention to an observed quality of airiness in Liu’s paintings, as well as the importance of intuition but intention when it comes to making art.

“That’s the major fun about painting, is that you can hold an intention, something in your mind, and then you can actually see it and people can sense it.”

— Inka Essenhigh

Sara Nickleson, Gallery Director and Artist

With a thorough understanding of Liu and her work, Senior Director of Library Street Collective and artist Sara Nickelson proposes a series of different topics that allow for a deep and intimate analysis of Liu’s practice and the concepts that drive it. The two discuss how recent lifestyle shifts—a move back to Taiwan from Michigan and the pandemic—have found their way into her work. Relevantly, Liu explains how isolation, solidarity, and apocalyptic narratives were already prominent themes in her work; in a sense, she is living in her research. Also highlighted in the talk is the myriad of dualities that exist within Liu’s work; for example, the combination of ancient and contemporary visual languages, the employment of cheerful colors to explore dark topics, and the foundational use of silk, a material that is simultaneously prestigious and kitsch.

“[G.E.] talks about the idea that challenges and traumas, illness and injury either ruin you or make you stronger, and that’s a really important part of [her] work—showing both of those sides of difficult situations.”

— Sara Nickleson

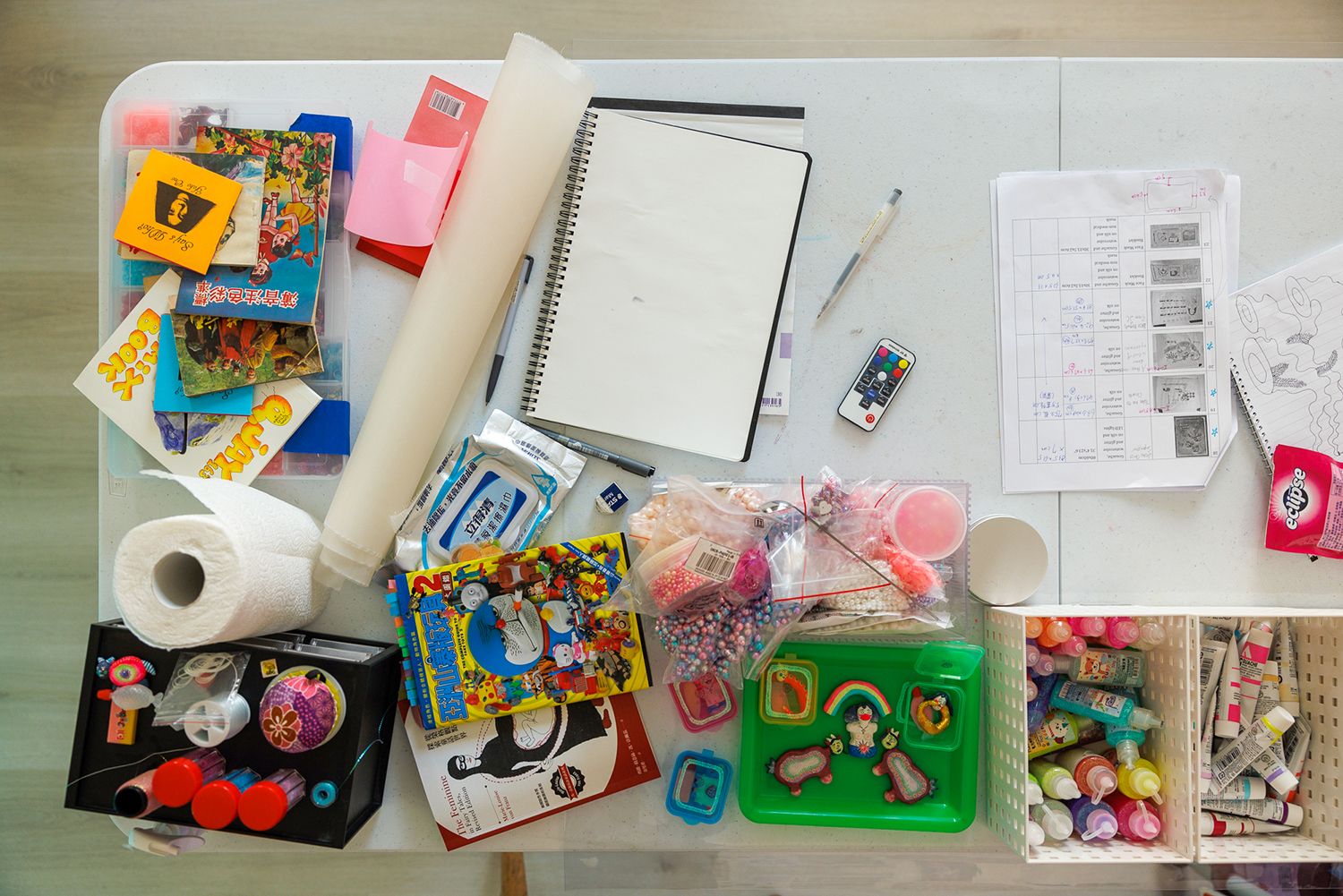

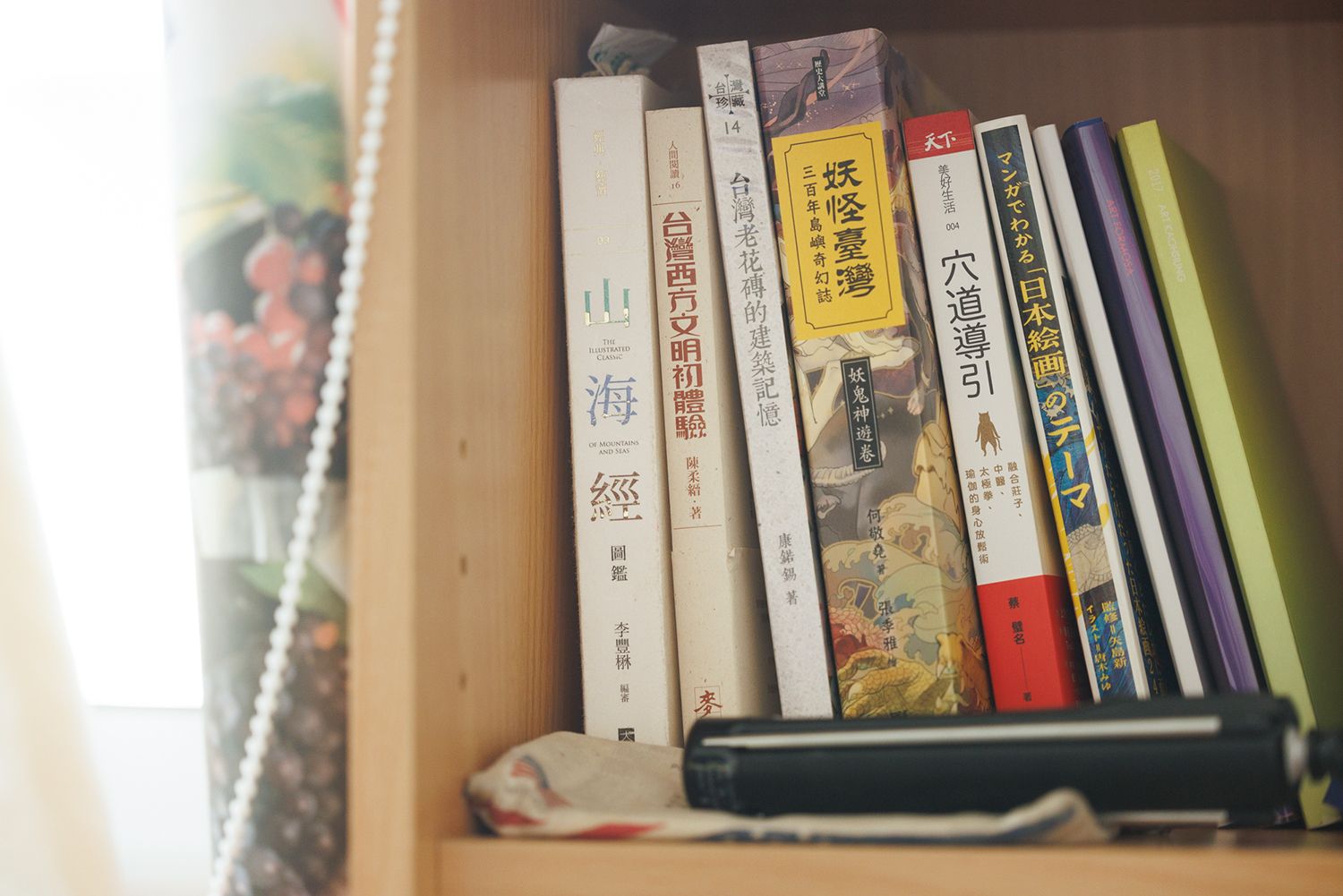

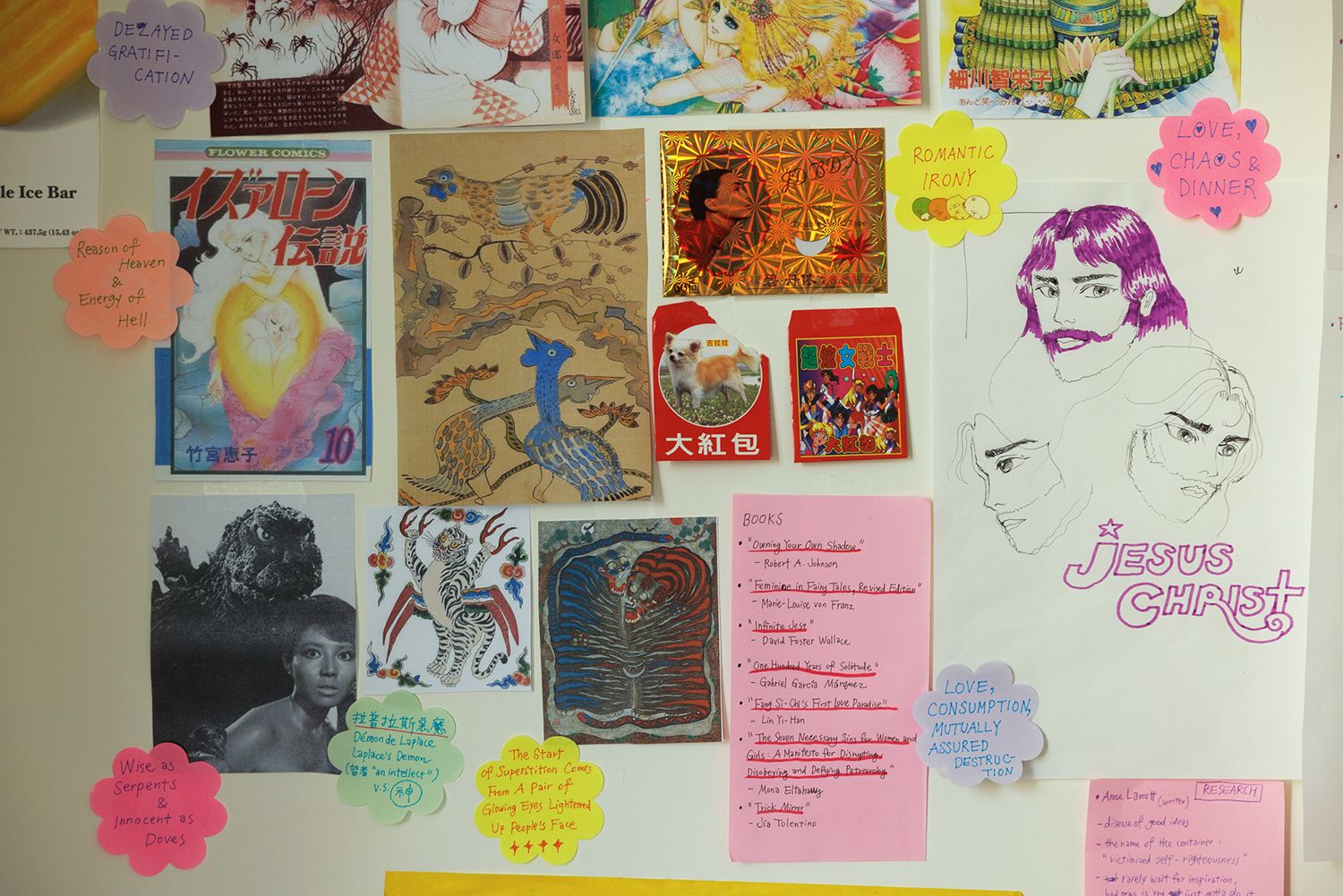

Studio Visit

READING LIST

Owning Your Own Shadow by Robert A. Johnson, Feminine in Fairy Tales and The problem of Puer Aeternus by Marie-Louise von Franz, The essence of Jung's psychology and Tibetan Buddhism: Western and Eastern Paths to the Heart by Radmila Moacanin, Psychology and Alchemy and Red Book by C.G. Jung, Infinite Jest by David Foster Wallace, One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Fang Si-Chi's First Love Paradise by Lin Yi-Han, The Seven Necessary Sins for Women and Girls: A Manifesto for Disrupting, Disobeying and Defying Patriarchy by Mona Eltahawy, Trick Mirror by Jia Tolentino, 厭女:日本的女性嫌惡" - 上野千鶴子 by Chizuko Ueno), and The Society of the Spectacle by Guy Debord.

“My studio practice focuses on building a mythological world as a coded satire of reality. The female characters in my work are an extension of myself, carrying qualities of self-deprecation and humor that entertain, yet encourage viewers to look deeper into the meaning of the work to challenge their perspective of the status quo.”

— G.E. Liu