Anatomy is a platform that dissects and narrows in on the various parts of an artist’s practice through the lens of their studio. This presentation will provide a glimpse into an artist’s background and process through a multimedia tour including video, audio clips, imagery, and conversations with fellow artists, curators, and other figures who have been influential in shaping and understanding these creators and their works. Anatomy's intent is to examine the myriad of ways in which an artist finds inspiration, merges art and life, and is driven by experience and the people that come into their world. We hope that this glimpse into the lifeblood of the artist’s practice will affect an even deeper reading of the works included and those yet to come.

Background

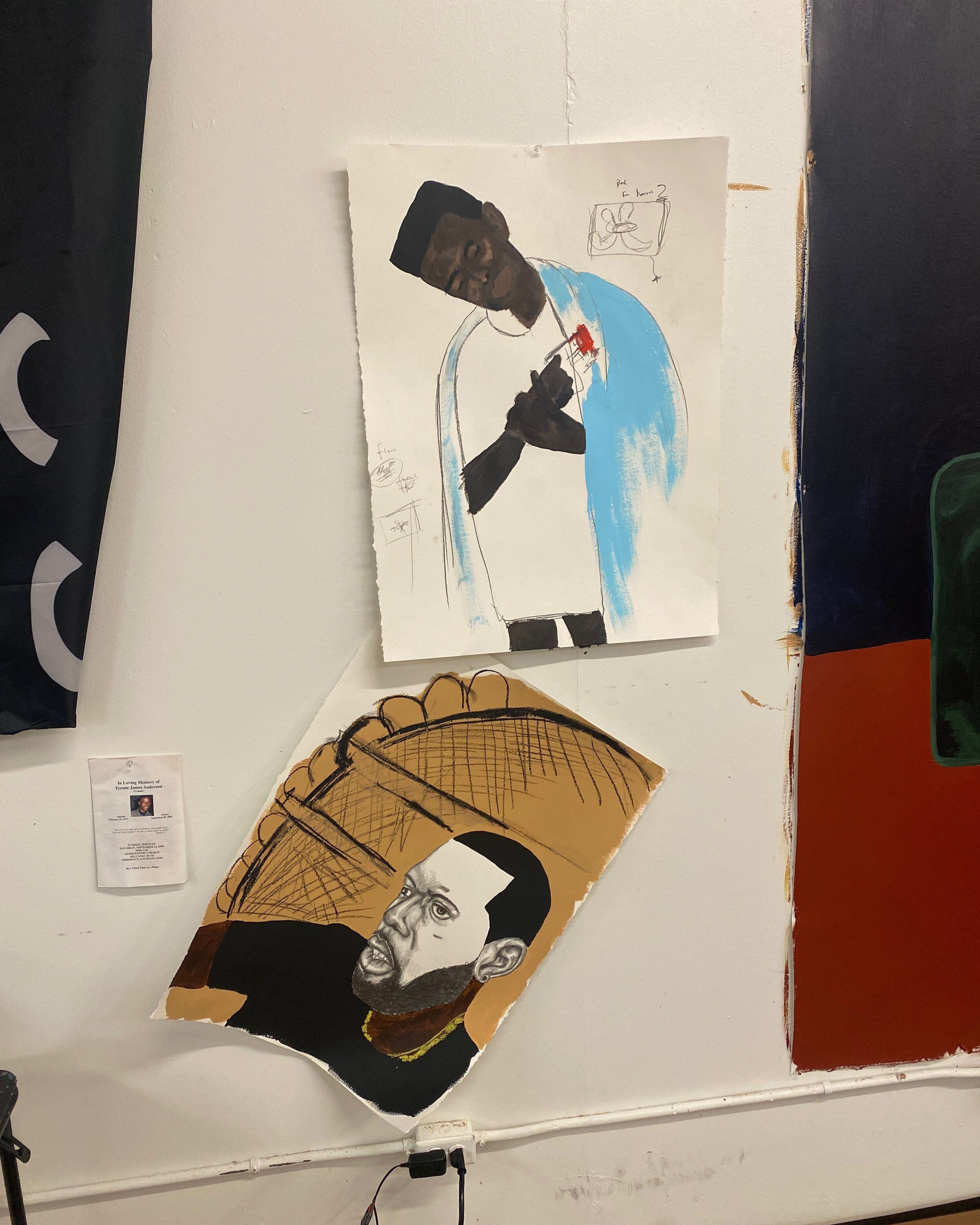

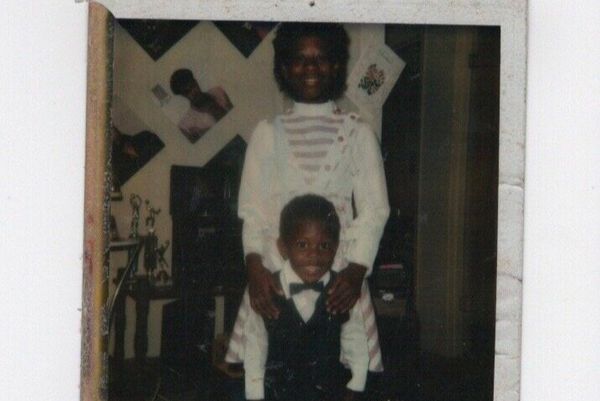

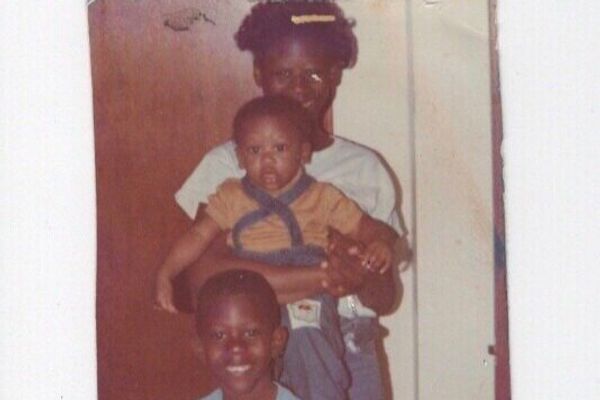

Jammie Holmes is a self-taught painter from Thibodaux, Louisiana, whose work tells the story of contemporary life for many black families in the Deep South. Through figurative works and tableaux, Holmes depicts stories of the celebrations and struggles of everyday life. Growing up 20 minutes from the Mississippi River, Holmes was surrounded by the social and economic consequences of America’s dark past, where reminders of slavery exist alongside labor union conflicts that have fluctuated in intensity since the Thibodaux Massacre of 1887. His work is a counterpoint to the romantic mythology of Louisiana as a hub of charming hospitality, an idea that has perpetuated in order to hide the deep scars of poverty and racism that have structured life in the state for centuries.

Despite the circumstances of its setting, Holmes’ work is characterized by the moments he captures where family, ritual and tradition are celebrated. His paintings incorporate text, symbols, and objects rendered in an uncut style that mirrors a short transition from memory to canvas.

Inspiration

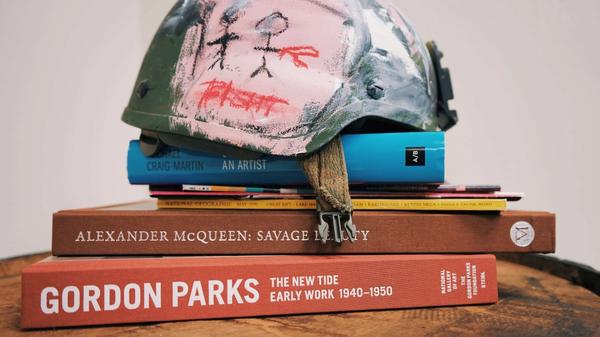

Gordon Parks — Untitled. Alabama, 1956. Photo courtesy of the Gordon Parks Foundation.

Holmes is a long-time admirer of the work of Gordon Parks, citing the photographer’s ability to capture the beauty and heroism of working Black Americans through many decades of discrimination. The painter shares a rare familiarity with many of the worlds that Parks presented throughout his career: Parks photographed the first black fighter pilots in the US Army, and Holmes himself served in the Armed Forces; Parks shot African American workers for Standard Oil, and Holmes worked for years in the Oil Fields of Louisiana - where he volunteered his position to save his colleagues from layoffs - before making his way to Dallas for work in a machine shop. And, just as Parks was, Holmes is a self-taught artist whose innate sensibility, empathy, and self-determination is the guiding force in his work.

“Gordon Parks is an inspiration to me because of his ability to capture moments that could be dark to some and happy to others. He just did what he loved. He told his story through a lens.”

— Jammie Holmes

Artwork

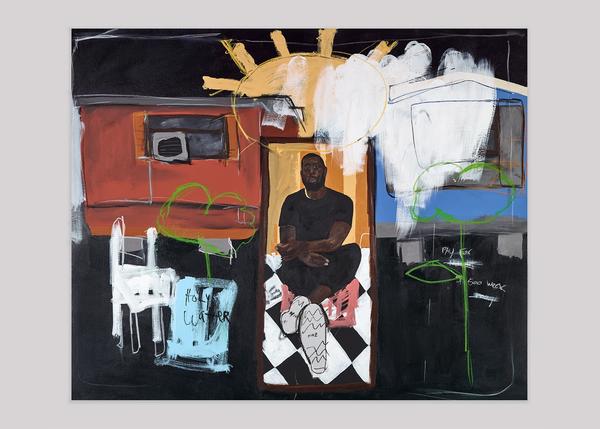

Sunny Days

Sunny Days

Acrylic and oil pastel on canvas

54h x 65.88w in

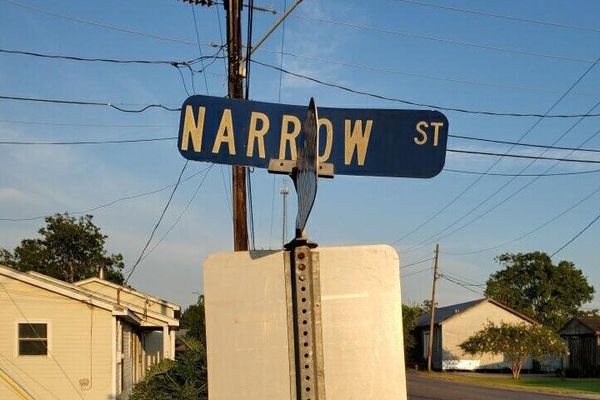

Sunny Days is a self-portrait of Holmes, his reflection presented in a mirror situated between two mobile homes where his family lived on Narrow Street. The artist has included the image of a mirror in past works, and its presence has come to symbolize the process of traveling into his past to revisit and reframe childhood memories as he works through healing from early trauma. Here, a bright sun is central in the work, a signal to his former self that a brighter future lies ahead.

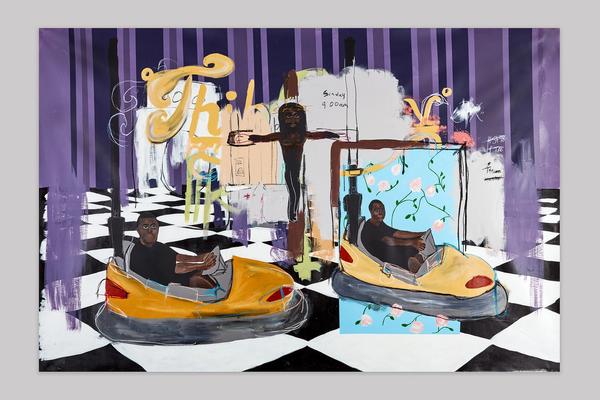

All on a Sunday

All on a Sunday, 2020

Acrylic and oil pastel on canvas

84h x 126w in

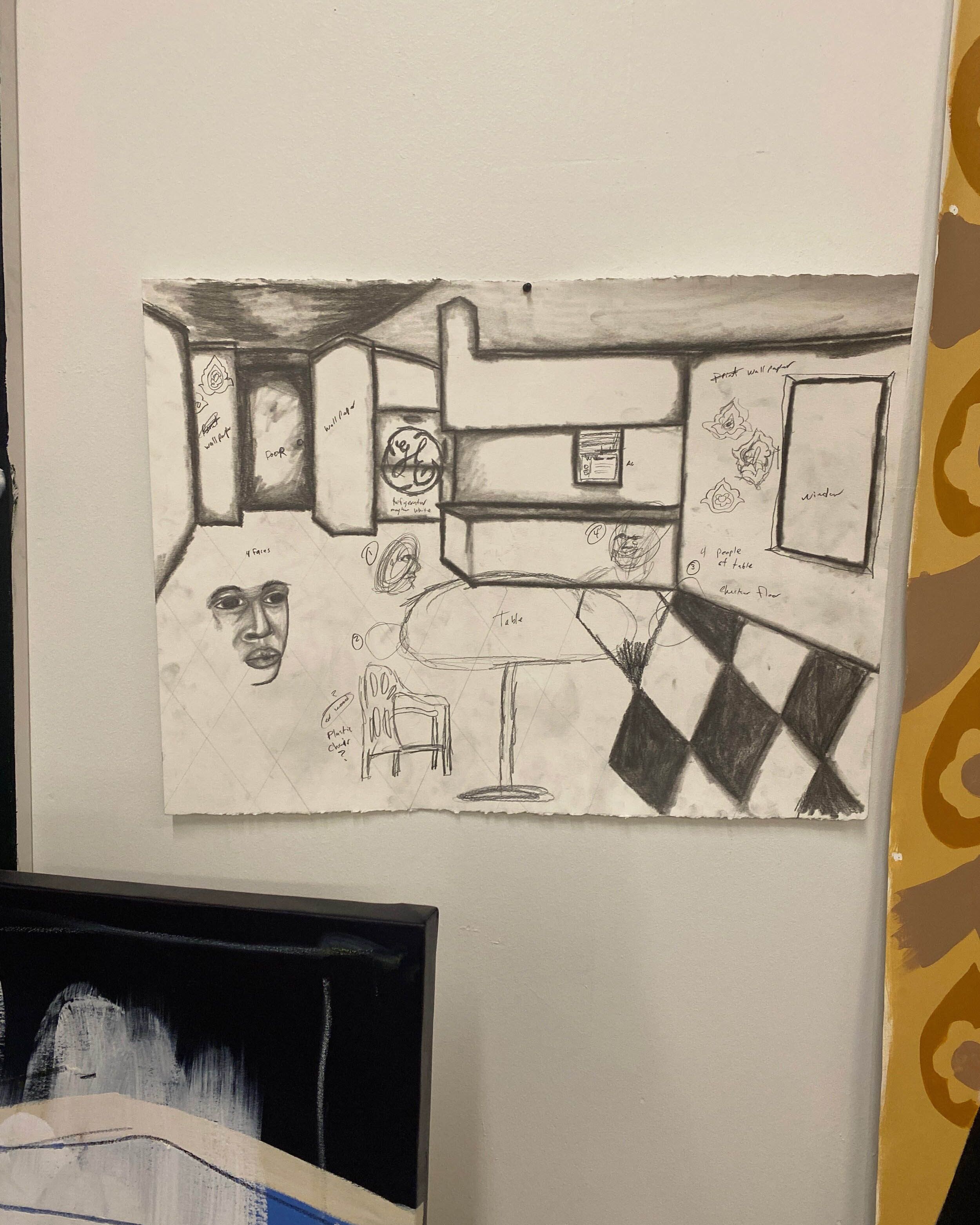

Spring in Thibodeaux brought the Fireman’s Fair. For Holmes, Sundays of his youth are a blur of days spent watching his mother do the wash in hair curlers as she tried to gather her kids for mass. If they behaved she might take them to the fair to ride the bumper cars. Sunday was always chaotic, and as a boy, he had conflicted feelings around religion that only grew as he did. Says Holmes, “Religion now means something different. We were living in a reckless environment, so church felt like a safe haven and a place to listen to life lessons. Our reverend lived in the hood and talked about real things happening.” Floral wallpaper is sometimes incorporated into Homes’ paintings as in All on a Sunday - often depicted just behind a male figure - meant to symbolize the need black men feel to present themselves as unthreatening in order to stay alive.

Second Childhood

Second Childhood, 2020

Acrylic and oil pastel on canvas

68h x 48w in

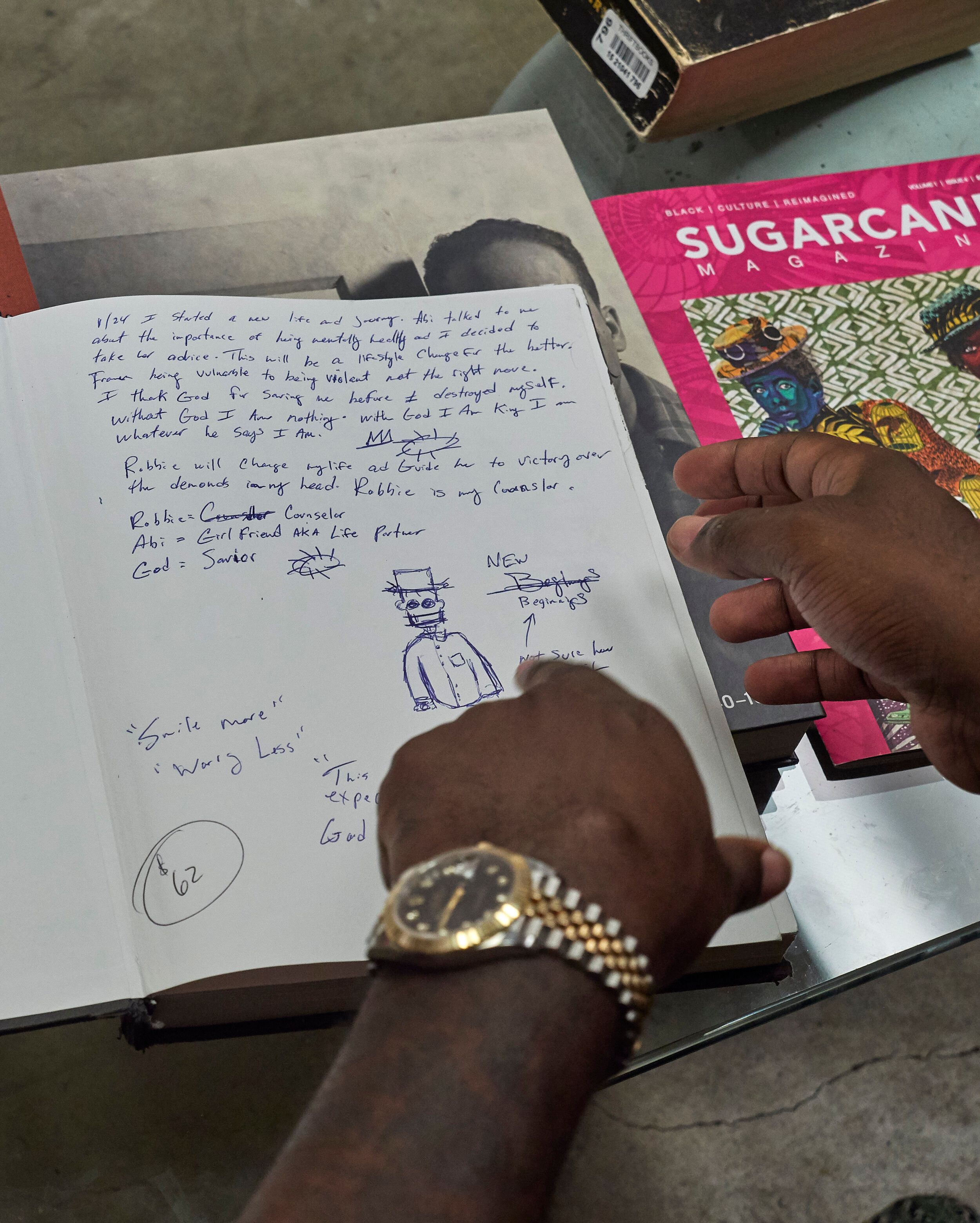

Holmes has spent the last few years working through past traumas, and much of the work he has done has paired cognitive therapy with artistic expression as seen in Second Childhood: “I’ve never had a birthday party, not ever in my life. With painting I can give myself a second chance.” His practice has been an immeasurable tool in his personal healing, and has brought purpose to his pain.

My Grandmother was an Usher

My Grandmother was an Usher, 2020

My Grandmother was an Usher presents a close bond between Holmes and his grandmother, who holds her Sunday church fan that depicts an image of Moses Baptist Church, where his family attended service regularly. Now in her 90s, Jammie is determined to spend another Sunday with her at mass in Thibodaux while she’s still able to attend. A blue color field with the text ‘water’ is a regular occurrence in his works, symbolizing baptism and rebirth, as well as the burial of a former life. The grey concrete grounds the work and represents a hardened past.

Ushers

Ushers, 2020

Acrylic and oil pastel on canvas

66h x 71.88w in

Holmes’ grandmother was an usher at his community church in Thibodaux, having been involved with the congregation from a young age. Ushers captures her in celebration with a group of women, bible and church fan in hand. Their passion is evident through the motion within the composition, as one figure raises her hands in exaltation. To Holmes, the piece recounts “the essence of what it was like at a southern mass.”

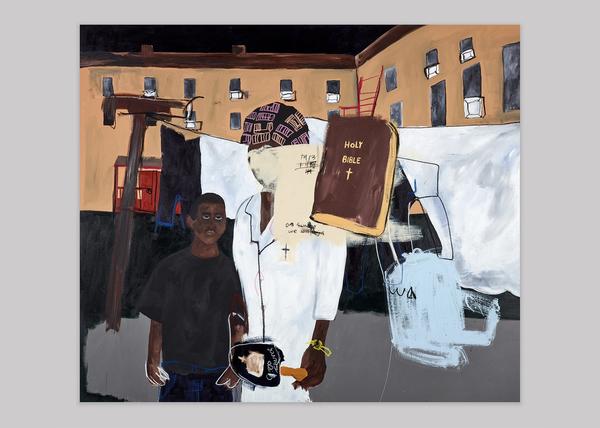

American Neighborhood #1 and #2

This set of paintings (American Neighborhood #1 and #2) reflects the pressure on children growing up in disenfranchised neighborhoods to ‘be strong’; take care of themselves and their families from a young age; and to normalize exposure to threats of crime, violence, or abuse. Holmes remembers looking up to the older guys in his neighborhood and wanting to be just like them, and the kids depicted in the two works fall within a vulnerable age, somewhere between 8 and 12 years old. Their gestures reveal two different sides of vulnerability, where one figure displays premature confidence while the other reveals reticence. Each has a pop gun nearby, reminiscent of earlier works by Holmes that paralleled kids growing up in rough neighborhoods to child soldiers in Sierra Leone.

“So many American kids are growing up in disenfranchised neighborhoods. We forget that rough cities are filled with kids who grew up too fast.”

— Jammie Holmes

Conversations

Derek Fordjour, Artist

Jammie and acclaimed artist Derek Fordjour met to discuss Jammie’s practice and influences. In their conversation, they discussed the tendency to classify southern art as ‘folk’; the factors that affect an academic vs. a nontraditional path; and the composition of Holmes’ Ushers is made available here for the presentation of Anatomy. Born and raised in Memphis, Fordjour relates to many of the factors that have shaped Holmes’ practice, and speaks of his interest in the expression of southern cultural specificity and its signifiers.

“I think (Holmes) is one of the few examples of someone who has a natural innate sense of design and color and form. He has worked, not in a classroom, but through observation. He has sharpened his visual acuity to a point that I’m a fan and I’m sure he has many more fans coming.”

Vivian Crockett, Dallas Museum of Art

Jammie Holmes sat down for a discussion during a recent studio visit with Vivian Crockett, the Nancy and Tim Hanley Assistant Curator of Contemporary Art at the Dallas Museum of Art. The two discuss Holmes’ beginnings as a painter, his deep connection to family in Louisiana, and themes that link the artist’s own experiences to his works for Anatomy. They also provide a glimpse into an upcoming collaboration with the announcement of an acquisition of Holmes’ work to the museum’s permanent collection.

“I think there’s something very powerful about the way that (Holmes) presents black masculinity; a way that people aren’t used to seeing. It’s a very complex portrayal.”

— VIVIAN CROCKETT

Amoako Boafo, Artist

Ghanian born and Swiss-based artist Amoako Boafo reflects on ‘Second Childhood,’ a painting by Holmes for Anatomy that he was deeply drawn to. Both artists’ works revolve around community, social struggles, and intimacy, and Boafo recognizes in Jammie a kindred spirit who also helped to support his family from a young age.

“Born to a fisherman father and a mother who was a cook. My dad would be away from home for long periods fishing while my mum left home at the crack of dawn to be on time to cook meals where she was needed. Being the eldest child I was forced to now be the caregiver and parent of my younger siblings. This painting (Second Childhood) deeply connects to the child inside me that still wants to enjoy his time that was missed on the playground.”

— Amoako Boafo

Studio Visit

“I call it sound checking my art. Sometimes if you look at the work long enough, your brain is going to bring up a memory. I like to listen for those moments to make sure it’s complete.”

— Jammie Holmes

Listen to Jammie Holmes' studio playlist.