Anatomy is a platform that dissects and narrows in on the various parts of an artist’s practice through the lens of their studio. This presentation provides a glimpse into an artist’s background and process through a multimedia tour including video, audio clips, imagery, and conversations with fellow artists, curators, and other figures who have been influential in shaping and understanding these creators and their works. Anatomy's intent is to examine the myriad of ways in which an artist finds inspiration, merges art and life, and is driven by experience and the people that come into their world. We hope that this look into the lifeblood of the artist’s practice will affect an even deeper reading of the works included and those yet to come.

Background

Working from stream-of-consciousness drawings to acrylic and airbrush, Willie Wayne Smith presents eight chimeric works that reinterpret personal and universal experience through a complex array of art languages that include abstraction, photo-realism, assemblage, and surrealism. Emanating from his atmospheric use of airbrush is a “state fair” aesthetic reminiscent of the visual culture in central Florida where the artist grew up exposed to customized cars, theme parks, and spray pigment t-shirts. Smith’s inclusion of ubiquitous objects—a concrete block, christmas tree, or beer glass—evoke both mundane and ceremonial use, set in landscapes that allude to sublime experience. The paintings call to mind the theological and art historical tradition of presenting the "lowly figure" in a moment of rapture, within a camp aesthetic. Placing a heightened focus on the inclusion of abstract signifiers, Smith aims to explore the possibilities of narrative and traditional value systems of painting through a cosmic lens.

Inspiration

Raphael

The Transfiguration, 1516–1520

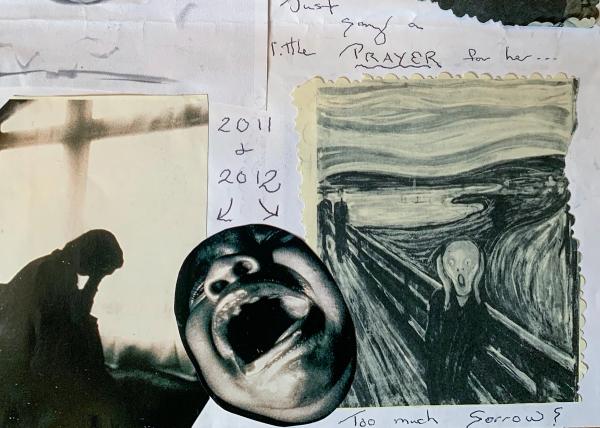

For his newest body of work, Smith cites inspiration from numerous artists including two who are seemingly dissimilar—Renaissance master Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino (Raphael) and German artist Martin Kippenberger, known for his wide range of styles. At the heart of this particular pairing of influences is the contrast in their approach to painting and beliefs around myths of artistic genius. Sir Joshua Reynolds said of Raphael in his Discourses (1797): “The excellency of this extraordinary man lay in the propriety, beauty, and majesty of his characters, his judicious contrivance of his composition, correctness of drawing, purity of taste.... Nobody excelled him in that judgment.” Smith looks to Raphael’s The Transfiguration to reinterpret man’s attempt to meet God and in the failed pursuit of these lowly figures, challenges the ideals of this Renaissance masterpiece, which was widely considered the perfect work of art for over 300 years. In the early 20th century, a new generation of artists began to resist Raphael’s artistic authority and considered The Transfiguration repellent—too crowded, dramatic, and artificial. In contrast to Raphael, who thought that art should translate ideals of beauty and faith, Martin Kippenberger insisted that art should connect with the everyday world. No subject was too sacred, nor too trivial, and his work drew on various points of reference—cultural, historical, personal—to convey satiric sentiments regarding the art world and its history. Kippenberger fought against the idea that painting was dead and challenged artistic "good taste" through "unrefined" and audacious works that would become known as his Bad Paintings. Like a number of artists before him, Kippenberger saw his artistic persona as an integral part of his work, but unlike those that created and sustained their own mythologies (Raphael, Picasso, Warhol), he was instead deeply reflective and self-deprecating. In a self portrait from 1988, we see the artist hunched on his seat in white underwear, his swollen belly and drooping shoulders suggesting abdication. A balloon covers his face in shame and self-loathing. Another important influence within Smith’s series is Frank Stella’s Moby Dick works of the 1990s, where abstract elements take on objecthood and suggest narrative play.

“[Martin Kippenberger] was someone who embraced the possibility of art as a limitless space… he was an artist who in many ways gave me the permission to constantly try new things, to embrace the possibility of failure, to understand that failure in itself is another possibility. ”

— Willie Wayne Smith

Self portrait, 1988

Extracts, 1993.

© Frank Stella / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Artwork

Within his work, Smith approaches the sublime as an entity that can be expressed through everyday objects and aesthetics, as well as through languages of abstraction. Complicating the pictorial space, his approach at the uncanny is clear through the amalgamation of disparate paint languages within one piece. It is important to incorporate "competing" styles and processes so as to disrupt the perceived illusion of the work, with the intention to belie or refuse existing value systems: “I think as humans, we have a propensity for creating value systems and belief structures that can really get away from the immediacy of an experience where things are unknown, so incorporating a language that disrupts whatever the other language might be implying is a way of, for me, dissolving the possibility of my work seamlessly reiterating an already cultivated belief structure around painting or the way it should be.”

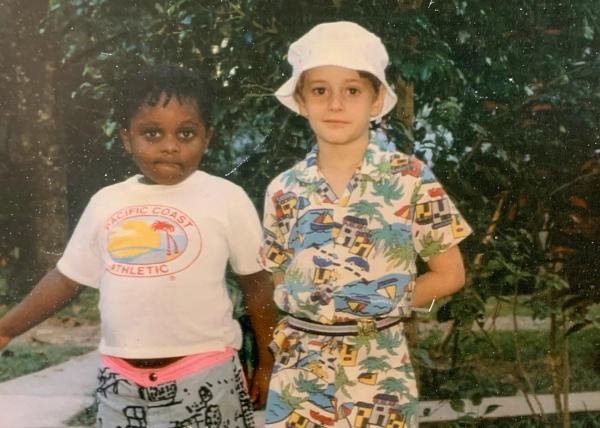

Growing up on a mission hospital compound in northern Haiti prior to moving to Florida, Smith experienced the well-meaning utopian intervention that is a real expression of an old colonialist existence; upon moving to the United States, there was a major shift in his reality. Through his paintings, Smith reflects on this cultural deviation, and processes his lived experiences in a way that they often become fantastical, self-mythologizing and larger than himself. With a deep-seated fascination in constitutions of popular taste, Smith constantly questions what should happen in a painting, ultimately using his multifaceted figures to express a worldview that is equalized and inclusive.

Just Breaking the Surface

Just Breaking the Surface, 2022

Acrylic and airbrushed acrylic on canvas

46h x 60w in

"Failed transcendence" is a phrase Smith has adopted in an attempt to encapsulate the overall concept that he strives to achieve in his work. This idea is in part explored through scrutinizing conceptual and visual qualities of ascension paintings, which are classically characterized by two zones: the upper heavenly zone and the lower earthly zone. Progressing in this vein, the subjects in Just Breaking the Surface are liberated from the constraints of gravity; one figure exits the pictorial space, leaving just their feet visible to the audience as their low-grade rubber flip flops cascade into the ocean, signaling the beauty of a possible ascent. This potential of phenomenological experience is further emphasized by the semblance of radiating light that emerges from the clouds and shines down on the scene.

While typical representations of ascension place godly figures in a moment of transcendence, Smith's figures are, intentionally, quite the opposite—average, meek, amateurish. To this point, Smith explains his belief that "all ascension paintings are failed in some way; there’s always this pointing at what can’t be depicted in the paintings because the ascension is post-existence, beyond what we know, so [he thinks] even attempting to achieve it in this very image-based-figure-ground composition, there’s a sense that [he's] not going to get that jaw-dropping moment where someone is awe-struck by the power of a new aesthetic in front of the painting." Instead of working to devise an impossible aesthetic, Smith depicts invented figures out in space where a glimmer of that kind of human experience might happen.

Details of Just Breaking the Surface, 2022

Acrylic and airbrushed acrylic on canvas

46h x 60w in

Listen to Smith reflect on this painting

0:00 |

Acting the Part

To create Acting the Part, Smith utilized a source image for the background which he scarcely manipulated from its original form. Depicted is a generic mountain scene with a woman rendered in soft focus in the foreground, the lowest portion of her body hidden from the eye due to the canvas’s limitations, leading the audience to wonder if she is grounded or floating in space. Distinguishing the painting from others featured in the presentation, Acting the Part is void of any hard-edged acrylic shapes that characterize much of Smith’s oeuvre. He often relies on these graphic symbols as devices to disrupt the imagined scenes’ believability, however here, it is the non-existent foliage or the red garment that melds and molds as if some sort of fungal mesh that hints at an imagined reality: “I was thinking in a silly way about mycelium, and these thoughts circling about nature’s own network of ideas—that there’s so much in nature we do not know.” Costumed in a bizarre expression of nature that enters the narrative into a whimsical sphere, the figure smiles fair-mindedly, commemorating her existential presence as a bountiful, complex, and unknowable being.

Small Getaway and Lifting Fog

Smith’s practice is chiefly an attempt for the artist to understand human beings to the fullest extent, and in turn, his own place within culture. All of the figures are entirely invented individuals, however, they are charged with the energy of Smith’s friends, family, and acquaintances as a means of realizing their existence and generating a palpable sense of empathy. Conventional figurative representations are subverted by Smith’s defiance of stereotypical beauty; emphasized and moreover celebrated are the inherent flaws of human nature that make a person individual.

In Lifting Fog, a subject dominates the foreground, lifting their shirt up to expose their stomach, potentially as to poke fun at their absurdist physique, or, alternately, perhaps in reference to a physical ailment; a number of possible narratives could be projected onto the action. Partially, this act of bodily exposure alludes to a condition of vulnerability, a moment of privacy—it is essential that these perverse states of being are considered in order to facilitate the figures’ discovery of their full potential. Like the character in Lifting Fog, the characters in Small Getaway serenely parade their awkward and rudimentary frames, while their passive expressions oddly ignite the possibility of many different emotions to be imagined, as if in-between states of feeling. Through the mundane performances of smoking a cigarette or drinking a glass of beer in seemingly divine settings, Smith marries the tension between the banal and the otherworldly, which he believes can exist simultaneously and collaboratively.

Monuments of Fleeting Feeling

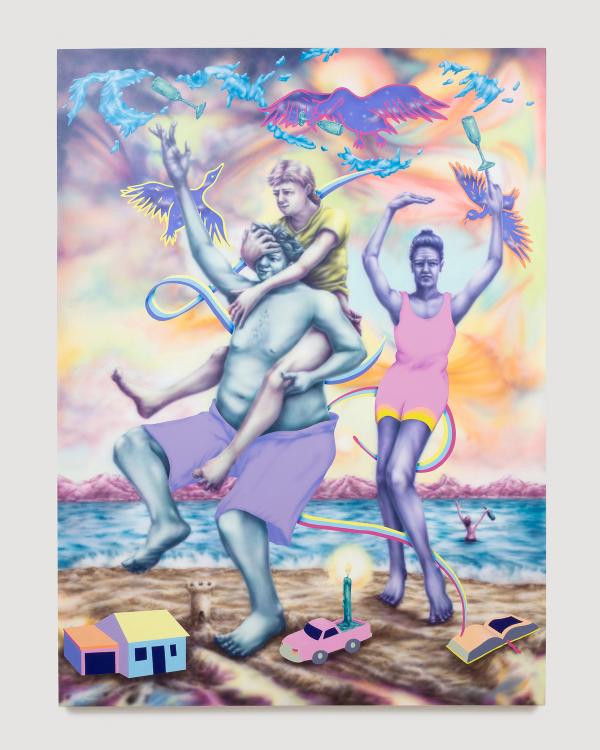

Monuments of Fleeting Feeling, 2022

Acrylic and airbrushed acrylic on canvas

96h x 72w in

Listen to Smith reflect on this painting

0:00 |

Monuments of Fleeting Feeling encapsulates Smith’s impulse to fuse various contrasting paint techniques into one work. A group of mannerist bodies rejoice amidst a divine shoreline, engaging in a moment of respite from reality on the bounty of what is not. A pastiche of sorts, here, Smith plays into a known narrative structure through the compassionate rendering of figure and landscape, but then subverts it through the introduction of hard-edged acrylic objects, such as a house or a car. These indecipherable, graphic forms play various roles: they are small signifiers of the quotidian life that, for a moment, the figures are escaping; at the same time, they are familiar objects lifted from mass culture and placed into unordinary settings, altering their established meaning and expanding their use. Moreover, Smith is fascinated with exploiting the plastic quality of acrylic paint to the point that it mirrors a commercial object in the same sense that, paradoxically, oil paint, idealized in the world of fine art, can be exploited to mimic human flesh. The work capitalizes on numerous dualities: of absorbing and obliterating art's hierarchical history; of glorified and (perceivably) amateur avenues of art-making; of necessity and possibility within routine and fleeting moments.

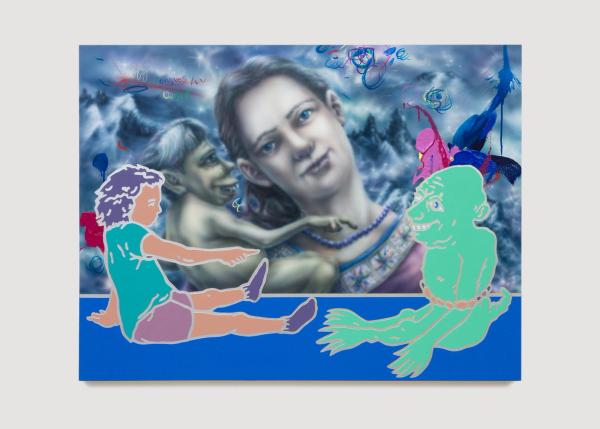

Appointed Companion

Appointed Companion, 2022

Acrylic and airbrushed acrylic on canvas

35h x 46w in

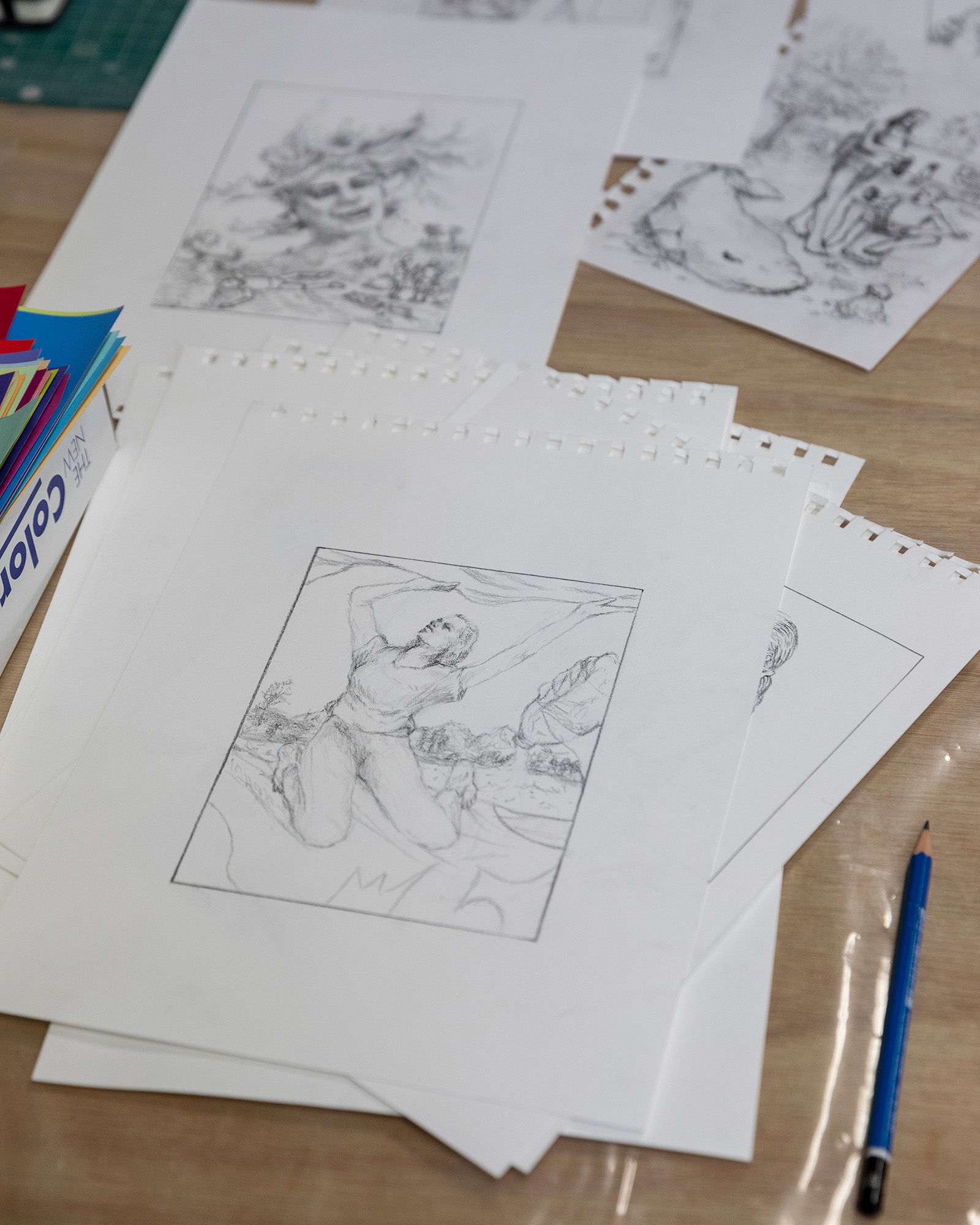

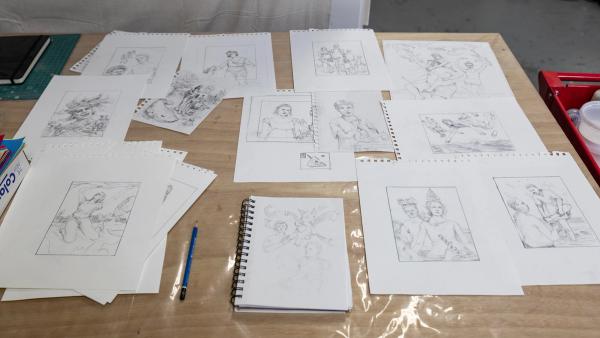

Smith begins his studies by making some simple marks and seeing what happens; there is not a type of figure or scene that he preemptively attempts to derive, the process is intuitive and most importantly an exploration of understanding where his compulsions lie. For Smith, constant and continuous research is essential—of the nebulas, the odd, the silly, the unexpected—to see where a painting can lead, afterwards reflecting on its meaning. With Appointed Companion, Smith was thinking about the often complex relationship between criticality and tyranny, and our ability to point to and isolate a problem in one instance, and comfortably coexist with it in another. The painting leans into the realm of mythology, expressed through the disproportionate gremlin-like figure that is far-fetched from reality. While typically a creature of such sorts exalts a negative or beastly connotation, Wayne paints the character as gentle and compatible, a friend to its counterpart rather than a nuisance. Visually, Smith alludes to a dream space as the female figure looks out at what resembles herself and the creature—roles reversed—rendered in his acute graphic treatment of acrylic paint; objects of such style are recurrently used as indicators of the phenomenological unknown.

Minor Holiday Drift

Minor Holiday Drift depicts a family unit of sorts; we may be looking at a matriarchal figure in the presence of her children, or alternately, a trio of siblings of all different ages. Mining interpersonal dynamics between a group of presented figures is not of primary concern to Smith, although he values both the maker’s and the viewer’s instinctive tendency to reflect on and draw such associations. Rather, Smith assumes an introspective posture, encouraging the exploration of one's individual relationship to the world around them. The trivial objects that accessorize the scene are ones that Smith continuously revisits in his practice. The cinder block is a notable example: a simplistic representation of form, it holds a potential use in terms of building a new structure, but when taken out of that universally understood context, Smith expands its use value, opening doors of wonderment and possibility.

Awash in Search of Awake

Smith regularly utilizes an airbrush in his work, particularly when rendering figures and spaces. The draw to the tool can be credited to a number of qualities, including his cultural association to it. Growing up in central Florida, Smith was accustomed to a visual culture of artifice and syntheticism defined by this sprayed, whimsical imagery of bright pastel color that constitutes his practice today. Alternately, he admires the tool for its power to bend the expectations of what instruments and processes should be used to make a painting. The atomized diffuse of the spray reflects the surface quality derived from the celebrated painting technique of sfumato, an effect that Renaissance painters actively aspired to achieve. Exemplified in Awash in Search of Awake, the paint device allows hard lines to become atmospheric as the figure's features seamlessly blend and conform to the surrounding natural elements. Considering the intrinsic qualities of his chosen medium, Smith romanticizes the kitschy and outlandish nature of the technique, challenging its objective contempt in the context of fine art.

“[These paintings] embrace an amalgam of different types of influence; I allow them to enter the work without judgement, knowing that there will be interpretations people have based on their associations,—of perceived value, of cultural value, of class differentiation—but feeling that these projections are going to somehow be a productive dynamic within the work, and not something to forcefully promote or try to make happen. ”

— Willie Wayne Smith

Conversations

Matthew Day Jackson, Artist

Matthew Day Jackson is a painter, sculptor, draftsperson, and photographer based in Brooklyn, New York. Through his multifarious practice, which includes collage, drawing, video, performance, and installation, Jackson engages with a wide range of subjects, from the historical and scientific to the futuristic and fantastical. At the core of his work is a deep interest in finding similarities within binaries and dichotomies, particularly the simultaneity of beauty and horror. Smith a former studio assistant of Jackson's, the two artists catch up as Jackson proposes a series of thought provoking-questions and observations about Smith's work. Points of conversation include how Smith's experiences growing up as they relate to class structures, identity and race influence his work, Smith's marvelous ability to create genuine empathy in his figures, and thoughts surrounding power complexes—the idea that art is not something to be pursued individually, but through a collective effort.

“[Willie's] own person is so open and accepting, and I think that the paintings, without ever using a single ounce of their radical nature, too have that same feeling… [this is] what I adore about the work.”

— Matthew Day Jackson

Andrew Paul Woolbright, Artist and Curator

Andrew Paul Woolbright is an artist, curator, and critic whose studio practice consists primarily of painting and drawing. His works appear collage-like, combining and layering disconnected subjects into chaotic and untethered landscapes, inspired by virtual experiences. Woolbright is the founder and director of the gallery Below Grand, formerly Super Dutchess on the Lower East Side of New York, and a frequent contributor to the Brooklyn Rail. Both educators in fine art, Woolbright and Smith discuss a myriad of topics through a historical lens, including artists' ability to inform the way we dream and see the world, as well as the way that technology—what tools were and are available to ancient and modern creators—affects the meaning that is ultimately derived from a work of art.

“I like the moments of rupture [in these paintings] because I always get a sense, looking at [Willie's] work, that there is a storage of history, but then [he puts] on the masks of history, too.”

— Andrew Paul Woolbright

Studio Visit

READING LIST

Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature by Félix Guattari and Gilles Deleuze, One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez, The Future of the Image by Jacques Rancière, The Love of Painting: Genealogy of a Success Medium by Isabelle Graw, Rabbit Redux by John Updike, Martha Quest by Doris Lessing, and Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe.

“I find it really important to not have reference material or historical images around in the studio while I work [so as to] face the void [and] pull something from it as a starting point.”

— Willie Wayne Smith