Library Street Collective has developed a unique digital connection between the visual arts and the built environment, incorporating aspects of storytelling, architectural history and an artist’s unique perspective through the presentation of SITE: Art and Architecture in the Digital Space. Each exhibition featured within this digital platform will respond to its environment, making connections between art and place. Library Street Collective has engaged renowned architectural photographer James Haefner to help realize the vision for SITE. Haefner is the co-creator of 'Michigan Modern: An Architectural Legacy’, and has been key in creating the architectural imagery and seamless digital renderings for SITE.

As a means to positively impact our community, Library Street Collective will be donating 10% of the proceeds from any works sold during SITE: Michigan Central Station to the MexicantownCDC, a community-driven program honoring Latino contributions to Detroit and Michigan. A leader in the revitalization of Southwest Detroit, their galería and café has organically developed as a community-centric location for over 80 art exhibitions, community meetings, local government awareness gatherings and more.

Library Street Collective is excited to present the third iteration of SITE: Art and Architecture in the Digital Space, set against the historic and transient Michigan Central Station. Formally dedicated in 1914, the station was an active rail hub until the cessation of Amtrak service in 1988. The Beaux-Arts structure was designed by the architects of Grand Central Terminal in New York, and was the tallest rail station in the world at the time of its construction. With a roof height of 230 feet, a main waiting room featuring marble floors, and 54-foot vaulted ceilings that echoed the sound of constant travel, the building is an architectural marvel.

Michigan Central Station

Once a location buzzing with arrivals and departures, reunions and farewells, Michigan Central had become one of the premier examples of Detroit’s ascent and decline, containing shadows of adventure, transformation, and relocation.

As the use of automobiles and highway systems became widespread, the station fell into desuetude over time. The structure was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1973, but became a magnet for urban exploration, scrappers, and graffiti in the decades that followed. After multiple sales and plans for revitalization (and building inspector recommendations for demolition), the Ford Motor Company purchased the building in 2018 with intent to create a headquarters for designing self-driving cars. Michigan Central Station will be the centerpiece of their innovation district, where mobility innovators and disruptors from around the world will develop, test, and launch new urban transportation solutions. Fortunately, the complex history of the grandiose structure is not over.

Installation Images

Travel was the locus around which Michigan Central Station was built, and became the central idea guiding the curation of the third iteration of SITE—not only physical travel from city to city, but the pull of the memory place, and nostalgia for the geography and experiences that have shaped us. We keep moving for so many reasons, but there is a chasm between those who travel to escape from the everyday and those who leave to escape persecution, violence, and poverty. We may travel through the same ports and passages, but our journeys are not the same. These vastly different experiences contrast hope and loss, excitement and fear, opportunity and necessity. In its many phases over a century, Detroit’s Michigan Central Station seems to embody this disparity. It is against this backdrop that we present works by Doug Aitken, El Anatsui, Hernan Bas, Sanford Biggers, Andrea Marie Breiling, Yoan Capote, Allana Clarke, Dominique Fung, Charles McGee, Allie McGhee, Jason REVOK, Jamea Richmond-Edwards, and Nari Ward, exploring ideas around the journey between here and there, migration from home, and the things discovered and kept along the way.

Installation Photography: James Haefner for Ford Motor Company

SITE Artists

Doug Aitken

Doug Aitken is a multimedia artist working between California and New York. Defying definitions of genre, he explores a multitude of media, from film and installation to architectural interventions, with a focus on creating moving works intended to catch the viewer unaware, eliciting responses that are unexpected and profound. In 2013, Aitken curated and produced ‘Station to Station: A Nomadic Happening’, a tour that travelled to 10 different locations by rail on a train the artist designed as a "kinetic sculpture that acts as a cultural studio.” At each stop, Aitken held a site-specific event featuring experimental film, food, and music performances by Charlotte Gainsbourg, Dirty Projectors, and Twin Shadow among others. More recently, a unique site-specific commission for the Donum Estate in Sonoma was created, titled ‘Sonic Mountain (Sonoma)’, which consisted of three concentric circles of suspended stainless-steel pipes whose differing lengths form a wave at their base, mirroring the free Euler-Bernoulli shape that describes a wind chime’s frequency. Known to have been used since the second century in India and China, and later in Ancient Rome, wind chimes create chance, inharmonic music. Of his spectacular take on this kinetic form, Aitken said: “I wanted to create a living artwork, a piece that would change continuously and be performed by the natural environment.”

Doug Aitken

Slow Wave, 2021

Chrome-plated aluminum, steel frame, resin,

rubber, stone

108 x 60 x 102 in

“'Station to Station' [was] a fast-moving cultural journey, a constant search over the new horizons of our changing culture. Grounded in some basic questions—Who are we? Where are we going? And, at this moment, how can we express ourselves?—our intention was to create a modern cultural manifesto.”

— Doug Aitken

El Anatsui

El Anatsui is recognized for his stunning large-scale assemblages consisting of discarded materials that visually resemble tapestries. Born in Ghana, Anatsui moved to Nigeria in the 1970s to teach at University of Nigeria, Nsukka, and left behind the plethora of available wood in Ghana, thus complicating his ability to continue creating wooden sculptures. As a result, his move encouraged more experimentation with different media. During the late 1990s, he stumbled upon metal seals from African liquor bottles, which began the incorporation of the found objects into his art. The shift in material began the creation of his best known works: large-scale sculptures consisting of thousands of repurposed metal pieces sewn together with copper wire. What makes Anatsui’s works particularly interesting and unique is the melding of Ghanian aesthetic and beliefs with abstraction, which is traditionally understood as having western roots. Anatsui interrogates legacies of colonialism through ideas of consumption, waste, and the environment as he contends with the ramifications of these ideas within his native continent of Africa. He is specifically discussing the importance of reuse and transformation within Africa, while also transcending the limits of place through commentary around global concerns.

El Anatsui

Alternative view of Delta, 2014

Found aluminum and copper wire

111h x 115w in

“I feel that each medium has its own language and changes the way that you want to express things. When you leave your normal domicile and travel, a lot of times your feeling for your original home grows stronger; the distance can make you reach new levels of empathy or feeling for it, so having a distance from any usual terrain provides an influx of ideas.”

— El Anatsui

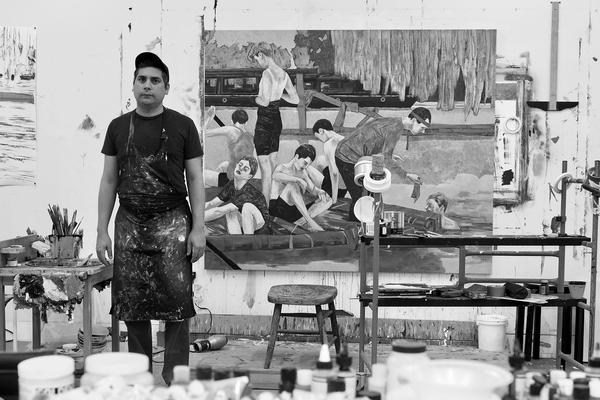

Hernan Bas

Hernan Bas was born in Miami, FL to Cuban immigrants, and grew up in the north-central region of the state. Since graduating from the New World School of the Arts in 1996, he has split his time between studios in Miami and Detroit, creating figurative works filled with allegory, whimsy, and decadence. Bas’ highly detailed paintings are informed by late-nineteenth-century Romantic art and literature, and grounded in the iconography of the young male dandy. From childhood, Bas has been enamored with the paranormal, and his works often read as exotic daydreams or a page out of the Gothic novels that inspire him. Alone or in small groups, his young protagonists navigate scenes of adventure, decadence, and enigmatic sensuality. The artist employs bright colors, maximalism, and expressionistic brush strokes to create lush and highly decorative scenes for his figures, calling attention to codified aesthetics and questioning what might define ‘gay art’ in the absense of overt sexuality. This indirect approach mirrors the way in which homoerotic content was engaged as subtext in literature, particularly in the work of some of Bas’ favorite writers, Oscar Wilde and Joris-Karl Huysmans.

Hernan Bas

The Day's Catch, 2021

Six panel folding screen, acrylic and silver leaf on linen mounted in a birch-wood frame with fabric backing

72h x 108w in

Courtesy of the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, Seoul and London.

“I feel a little schizophrenic when it comes to inspiration. If my inspirations aren't obvious in the work, I feel more sane. Ultimately, I’m drawn to great stories, and I have an appetite for them that leads me all over time and space.”

— Hernan Bas

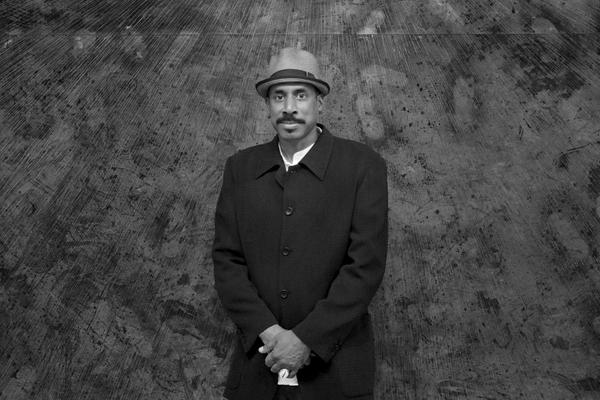

Sanford Biggers

Sanford Biggers is known worldwide for a robust art practice that confronts social and political narratives while also examining the contexts that bore them.

In 2014, the artist initiated a series of bronze sculptures entitled BAM that memorializes and honors victims of police violence in the U.S., pointing towards recent transgressions and elevating stories of specific individuals to combat historical amnesia. Each sculpture is named and dedicated after unarmed victims who have died at the hands of law enforcement.

BAM (for Michael) is dedicated to Michael Brown, who was shot and killed in 2014 in Ferguson, MO.

The series is composed of fragments of wooden African statues dipped and veiled with thick wax and the ballistically ‘resculpted.’ Biggers then casts the remnants into bronze, a historically noble and weighty medium. For Biggers, this process bestows honor to the damaged figure, allowing it to become a “power object” that, along with the memory of each victim, is worthy of veneration and a stark reminder of the work that needs to be done to fight injustice.

“I often say time is malleable, but the reception of an artwork is malleable too. When the culture changes, the view and the way you see that work, your perspective, changes. It’s sort of daunting and intimidating, but at the same time very fascinating, extremely fascinating”

— Sanford Biggers

Andrea Marie Breiling

Andrea Marie Breiling was born in Phoenix, AZ, and spent much of her career in Los Angeles. Her earlier abstract works drew from the aesthetics and ideas within the history of Action Painting, but a recent move from LA to New York has energized an exciting deviation in her practice. In an effort to push the boundaries of abstract painting by creating work without the use of a traditional paintbrush, the artist picked up a can of spray paint to experiment. Her current practice has been referred to as less like graffiti and closer to the atmospheric, hazy works of JMW Turner. One review of Breiling’s September 2020 exhibition with Night Gallery said that the works felt as if the artist had breathed them into existence, “...like (she) made them by exhaling. They surround you like an atmosphere.” This ethereal reading perfectly aligns with Breiling’s experience during the creation of the paintings: “I finally felt the work becoming more of a psychedelic experience, wrapping up the viewer like a drug; a full-body experience, beautiful and emotional and sublime.”

“Making paintings is always a transcendental experience. I decided to pull back, to travel and play with materials and figure out how to accomplish this.”

— Andrea Marie Breiling

Yoan Capote

Born and raised in Havana, Cuba, Yoan Capote has spent his life on the island and continues to live and work there, despite a fraught relationship with the place he calls home. Using sculpture, painting, installation, photography, and video, Capote creates parallels between the symbolic meaning of found and sourced objects and the human psyche. It may be the challenging conditions and contradictions of life in Cuba that keep him there, creating work with a deep connection to the country, and exploring oppression and migration. The objects he selects are chosen with purpose and metaphor in mind, such as within his ‘Palangre’ series of seascapes, which he fabricated from thousands of hand-wrought fish hooks. From a distance, the works read as classic paintings of sea meeting sky, but upon closer examination, the severity of Capote’s materials are poignant. As the artist describes, the ‘Palangre’ pieces are something of a memorial to the many thousands of Cubans who have taken to the water in hopes of a better life in America: “the fish hooks are a direct allegory of the water, but also an allegory of a trap, or seduction, pain or death… I wanted this series to embody that risk and that frustration; the risk of dying in the water, the frustration of accepting that geography and politics decide the limits of individual liberty.”

Yoan Capote

Muro de Mar (umbral), 2020

Fish hooks, nails, ink and enamel on carved recycled wooden doors

83h x 136.25w x 4.75d in

“Reducing the sea to a straight and narrow path is impossible—the probability of surviving or succeeding in the journey is very narrow, very compressed. I’m concerned with the idea of magnetic north, of trying to seek a universal point of guidance while surrounded by the sea.”

— Yoan Capote

Allana Clarke

Trinidadian-American interdisciplinary artist Allana Clarke focuses intently on contending with the complexities of Blackness and examining colonial and post-colonial motifs. Her research-based practice consists of video, performance, photography, and sculpture, in which she incorporates socio-political and art historical text. Personal narrative is also a foundational element of her practice as she navigates American culture through Trinidadian roots. With an understanding of Afro-Carribean politics in conjunction with American ideas, Clarke’s work often challenges viewers to rethink ideas of womanhood and Black identity throughout the diaspora. Instead of delving deeply into stereotypes, Clarke focuses on redefinition in terms of breaching boundaries and ideas of belonging, often utilizing her own body as the platform for her expression.

“Can we exist in a space of action and intersectional transformation? I do not know. I am trying to do that, but how do you model something that you’ve never seen, necessarily?”

— Allana Clarke

Dominique Fung

Dominique Fung is a Canadian artist living and working in New York City. She was born and raised in Ottawa, Canada, the daughter of first-generation parents from Shanghai and Hong Kong. Like many other children of first generation immigrants growing up in the west, Fung spoke two languages—English, like her peers and friends at school, and her parents’ native language at home. Having lived all her life in North America, her sense of Chinese heritage was largely informed by the vessels and objects on display in her home as well as those in Asian Art collections at the museums she visited, in particular at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Fung cites her analysis of the Cantonese term ‘jook-sing’—a pejorative referring to persons of Chinese descent who live overseas and identify more with western culture, which evolved from the word for ‘bamboo pole’—as an early inspiration for her work. The term suggests that Chinese people born in the west are hollow like bamboo poles, signifying the lack of Chinese culture in their knowledge. Fung realized that the museum relics she admired and identified with were jook-sing like her, separated from their origins by time and distance. The relics were also coveted and reduced by the west, where objects once held in high regard for their mastery and importance in religious or cultural observance are copied and mass-produced as a shadow of the original. The use of vessels in her work became of great importance to Fung, who has also used such objects in paintings that explore Asiastic Femininity and the dangerous fetishization of Asian women in America.

“I’m definitely not thinking about futurism; it’s more about looking to the past and how we can present ourselves in the present. These objects [I paint] are protagonists to what’s happening in the picture plane. They have these untold stories and come alive to talk about our own humanity.”

— Dominique Fung

Charles McGee

When Charles McGee was ten years old, his family moved from South Carolina to Michigan, adding to the millions of African Americans who migrated from the Southern United States to more urban areas in the American Northeast, Midwest, and West throughout the twentieth century. Known as the Great Migration, estimates of about six million African Americans migrated from the south moving toward more opportunities outside of sharecropping and in efforts to escape racial segregation. When McGee moved north, he brought with him a fledgling understanding of the harmony of nature and an inquisitive spirit relating to relationships of people. He used artwork to examine and discuss his observations and ideas. Early in McGee’s career, he produced a number of realistic portraits focusing mostly on highlighting Black women and motherhood. Yet, he soon became more interested in abstraction, oftentimes featuring abstracted figures. Many of his works, however, focused completely on line and color, with no recognizable nods to figuration. He often utilized mark-making, lines, shapes, and layering to depict movement and focus on the energy of the work. Throughout McGee's extensive career, his practice shifted multiple times, ebbing and flowing from vibrant color to black and white and back again; through varying degrees of abstraction, his work invariably celebrated the creative nature of humankind and focused on what unites us all.

“The fact that you are born and exist in a particular geographic location is going to cause a chain of events that starts from birth or even before birth—what happens along the way is you take the purity of where we came from and it starts to metamorphosize as we grow and as we assess information, process the information.”

— Charles McGee

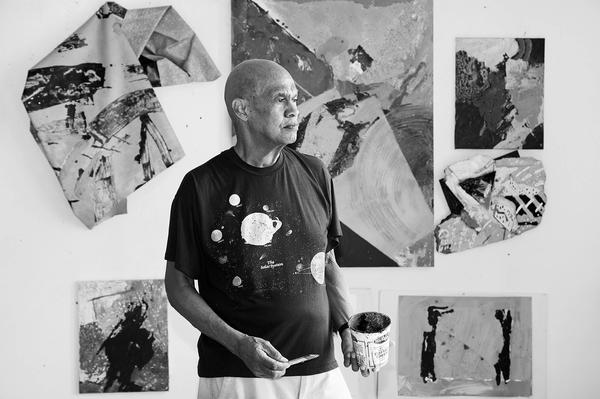

Allie McGhee

Allie McGhee was born in Charlston, W.V. in 1941 and moved with his family to Detroit when he was ten years old. Beginning his artistic practice with representational work, McGhee shifted to abstraction in the late 1960s, inspired by the improvisation and emotion of jazz, as well as a fascination with science and the cosmos. Fearless experimentation is at the core of his process, and at 80 years old, he continues to play with new materials, concepts, and techniques. He admits to spending 364 days a year in his studio (“every day except Christmas”), beginning work early and ending the day at dusk: “You begin slowly, until you’re deeply involved in your work. Can’t put a time clock on it. The sun is the master because it illuminates the color.” This guidance by the rhythm of the earth’s cycle aligns with his love of natural science and astronomy, and similarly, he allows his materials to lead him in his practice. Always curious, McGhee's enthusiasm to take on any surface that will hold paint positions him as a pioneer of the Detroit aesthetic, where through circumstance or an exploratory spirit, found materials are patched together to create sculpture and layered, complex painting.

“Every day, you begin slowly until you’re deeply involved in your work. Can’t put a time clock on it. The sun is the master because it illuminates the color.”

— Allie McGhee

Jason REVOK

Jason REVOK is a Detroit-based artist who cut his teeth as a graffiti writer in Southern California. In the pre-internet 80s and 90s, he and his crew enjoyed the underground nature of graffiti culture, taking 35mm film of their work and sending it out to independent magazines and other artists around the world. His skill and willingness to paint elaborate walls in places others would never touch (due to the visibility of a particular location and the risk of being caught) earned him a massive following, and he was invited to cities all over the globe to paint. Because of graffiti, he saw the world, and in 2011, set his sights on Detroit as a place to participate in the explosive graffiti scene as well as begin to develop a unique studio practice. “Everything I’m doing now is very much a product of the past,” says REVOK, recalling his time spent in the city. “I started going out and sampling little bits of the city and taking them back to my studio and reshaping them and assembling them into a new thing or object. It was about Detroit as much as it was about me.” He worked in assemblage in order to step back from painting and his graffiti-based instinct; after a few years, he was back in LA with the birth of his daughter and felt ready to look at paint from an entirely different perspective. Using some tools from his past in unique ways, REVOK has developed a language that is rooted in graffiti but builds a bridge to his love of minimalist artists like Frank Stella and Sol Lewitt. Now back in Detroit with his family, he continues his search to find balance between the anarchy of his past and the harmony and peace of mind he seeks in the present.

“I started going out and sampling little bits of the city and taking them back to my studio and reshaping them and assembling them into a new thing or object. It was about Detroit as much as it was about me.”

— Jason REVOK

Jamea Richmond-Edwards

Jamea Richmond-Edwards’s paintings and collages are deeply rooted in her upbringing in Detroit, Michigan and her ancestry. Richmond-Edwards’ female-centric work consistently reveals the influence of her mother, grandmother, and sister. From aesthetic choices to the agency Richmond-Edwards affords her figures, the vivacious and bold characteristics that appear in her works through color, density, and layering are a direct reflection of the influences these family members have had on her life. Ultimately, Richmond-Edwards creates imagery that narrates stories of Black and Indigenous womanhood with themes of identity, luxury, local fashion, and agency. She situates these works on a bed of understanding her genealogy and the movement of her ancestors throughout the history of America.

“Luxury, for me, is about having agency over your own body and having the agency to move and be free. It's deeper than clothes. I'm looking at my upbringing and the experience of my people from a different lens.”

— Jamea Richmond-Edwards

Nari Ward

Nari Ward’s artistic practice clearly communicates the influence that location can have on the ways in which one identifies and focuses their attention. Ward is best known for his large-scale installations constructed of found objects that highlight major social and cultural issues, especially within inner cities. A native Jamaican, Ward moved to New York during his formative years, experiencing the poverty and urban blight of the city, but specifically understanding the cultural tumult. Ward reveals his concerns through his artwork and encourages viewers to find their own relevance within the pieces. His installations become architectural symbols that breathe new life into everyday objects people have discarded or left behind. For Ward, these objects represent the streets he consistently traverses, and he builds narratives through their connections, focusing on themes of race, poverty, and consumer culture.

Nari Ward

Mango Tourist, 2011

Foam, battery canisters, Sprague Electric Company resistors and capacitors, and mango pits

120h x 19.75w x 19.75d inches each (approximately)

Courtesy of the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, Seoul and London.

“'Mango Tourist' [is] made out of foam, mango seeds, and capacitors and conductors, which are analog electrical parts. [The] piece [is] really about power… if you mined the title, it’s talking about support, economic growth, coming not from a local grid, but from a tourism grid. Power that’s not local, but coming from somewhere else.”

— Nari Ward